#GetBloodyTalking

Let's ignite the conversation about periods in the UK. It's about bloody time.

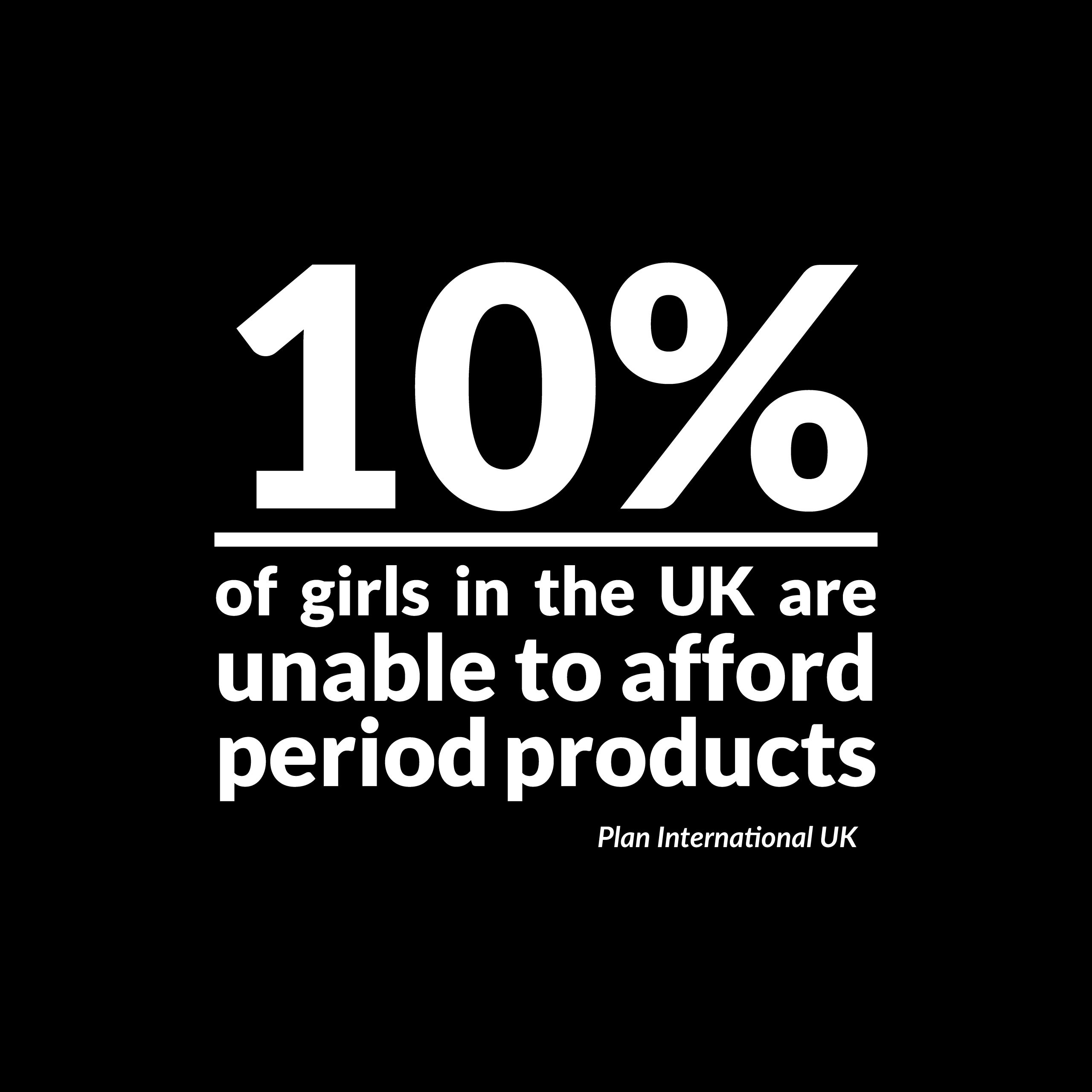

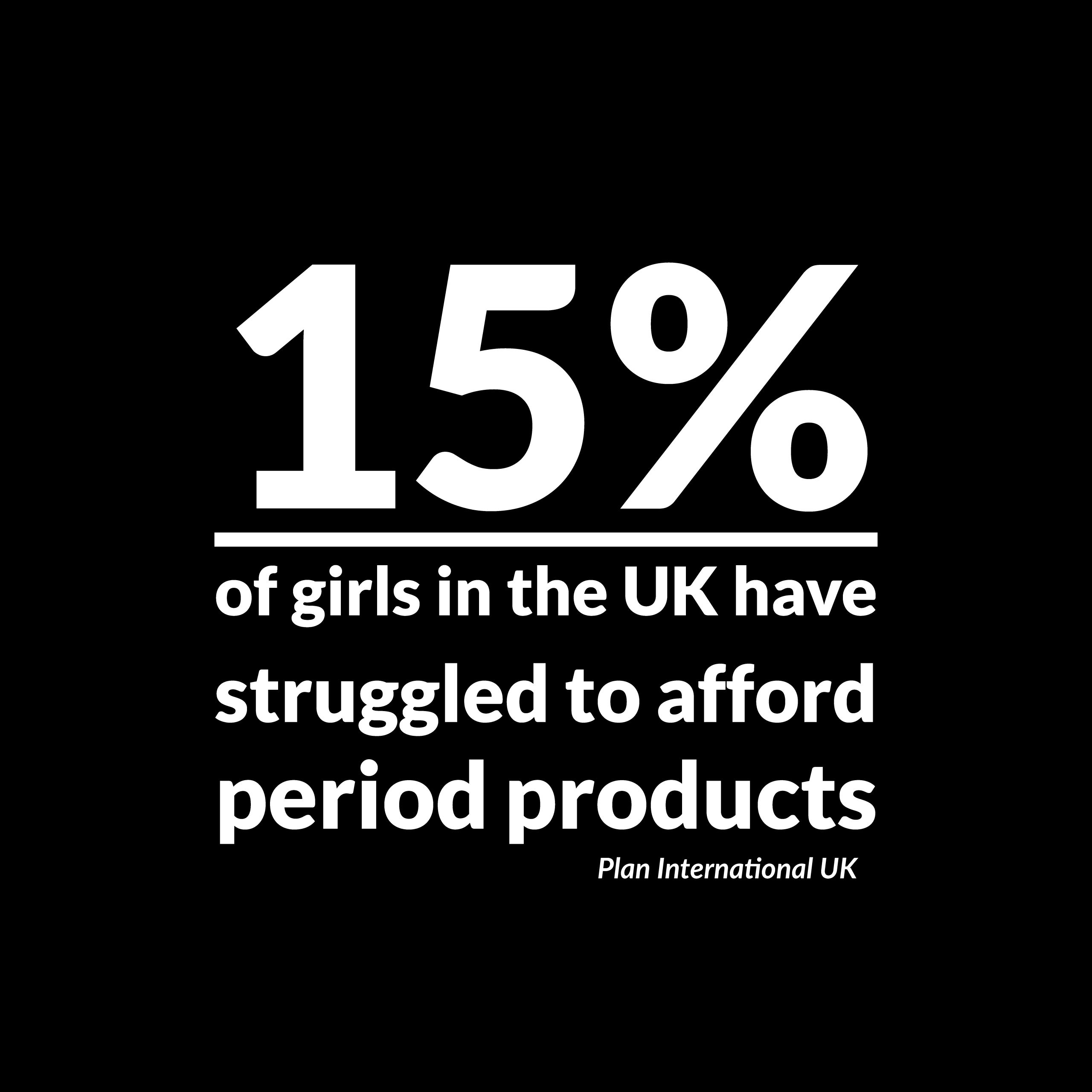

According to a 2017 study carried out by Plan International, a tenth of girls in the UK are unable to afford period products. One in seven struggle to find the funds to buy tampons and pads.

Menstruation is a natural bodily function, but speaking to people who have suffered with period poverty, and charities that provide help, it's clear that the stigma surrounding periods puts a blockade in front of any possible change.

Our collective refusal to talk about menstruation perpetuates problems that many girls and women go through.

It’s time we change that. It’s time that we #GetBloodyTalking.

‘Period poverty’ means being unable to access sanitary products and having a poor knowledge of menstruation often due to financial constraints.

Period poverty affects thousands of women and girls across the United Kingdom. Millions across the world. But what does this actually mean to those going through it? Lesley, a 32 year-old mum of three from Leeds opens up about her harrowing story of living through period poverty, and how it affected her life.

Lesley's Story

It’s a memory that will live with me for the rest of my life. I remember the streetlights being so bright. It was night, but it felt like there was a sun hovering right above me.

Dazed and confused, the only thing I could focus on was the next step in front of me. My breathing was tight, as though someone had pulled a belt tightly around my chest.

I was bleeding. It was so obvious. I didn’t have any period products and it was everywhere. Everyone could see.

The lights seemed to get brighter. I was mortified. Embarrassed. Ashamed.

I was 21 at the time and had no-one to turn to. There were many underlying factors to my situation, but only eight months before, I’d left my boyfriend and children. I’d roamed the streets of Leeds since.

My life was in ruins. Any relationship I had with anyone had completely crumbled. I'd fallen completely off the rails.

"I was mortified. Embarrassed. Ashamed."

My main concern at that point was where the next drink was coming from. Where my next fix was. Anything else was secondary.

Usually, I could find a public toilet and use toilet paper as a makeshift tampon. But that night, everything was closed.

I remember standing in a shop, looking at tampons. The price tag broke me. The £2 in my pocket would be needed for food or a fix, not tampons.

Tearing off a corner of a newspaper, I pushed it off for another day, only to find myself a few days later stumbling down the street, looking for help. But I didn't know where to turn.

Maybe I was too ignorant, or too uneducated. I wasn't aware of any charities in Leeds at the time. I still don't know of any organisations back then that could've helped me.

I hadn’t spoken to my Mum in months. Our relationship was in turmoil but I had to bite the bullet, swallow my pride and turn up to her home. Every emotion rushed through my body as I struggled to her front door the following day.

Would she slam the door in my face? Would she tell me to go away and never come back? Would she be ashamed too?

The door opened; my heart dropped but she hugged me. She stepped forwards, cried and hugged me. She told me she loved me, and that everything would be okay; that she’d clean me up and buy me products. That she’d look after me.

I understand that this was self-made poverty. I’d brought all of this on myself. But the experience of walking through Leeds, bleeding, for everyone to see was traumatizing. You can imagine how much damage it’s done, with it still scarring the back of my mind over a decade later.

Lesley and two of her three sons.

Lesley and two of her three sons.

At the time, I thought I might be an exception. That I was the only one rolling up toilet paper in a public toilet, only because I was addicted to drugs. But through my experience, I’ve met so many different women going through such a similar thing. But girls and women in all walks of life.

Women and girls fall into period poverty for many different reasons. Mine was an abusive relationship. Another lady I met couldn't afford tampons because she was caring for her dying mother, and didn't have time to work. Another simply didn't know what her period was.

I’m completely clean now and have been for nearly a decade. I don’t go near drink, and certainly not drugs.

My experience has taught me to never be judgemental. To never assume anything about anyone. We're all the same, just trying to get through this life in the best way we can.

I'm so lucky to have three amazing children. They're the spark of my light now.

But those lights from that night are permanently burnt into the back of my retinas. The faces of those passing by are imprinted into my mind forever. That shame etched onto my heart.

If we can do anything now, it's educate and talk. Let's stop shying away from this topic and actually combat it. Together. Because we all have a role to play.

It's no secret that over half of the population menstruate at some point in their lifetime, yet there’s still a huge taboo around the topic. The conversation about periods is muted, even within the female community.

“The problem with women is we’ve all been through periods, we all go through it,” Katie, a psychology student from Sheffield said. “Because of that, I think we just expect each other to get on with it. Those who are able to just get on with life when they’re menstruating sometimes expect others to do the same, but it isn’t that easy for all of us.”

Society has created a stigma around menstruation. Despite it being a natural bodily function, many see it as dirty or shameful. Others simply don’t like to talk about something that’s personal. This results in people going through period poverty suffering alone. It forces women to hide period products up their sleeve when going to the toilet, or putting tampons at the back of cupboards where no-one else will see them.

Swedish journalist Anna Dahlqvist opens up about this in her book It’s Only Blood. She admits, in the book that she doesn’t like to use the term ‘period’, even as a woman and that she feels ashamed that she cannot control her own body.

"My shame as an adult: I hesitate to say the word ‘period’. My voice falters. It is as if it diminishes me to admit that I menstruate; it makes me vulnerable. I am governed by a biological phenomenon that I cannot control and that separates me from the others, those who do not menstruate – those who are in control.”

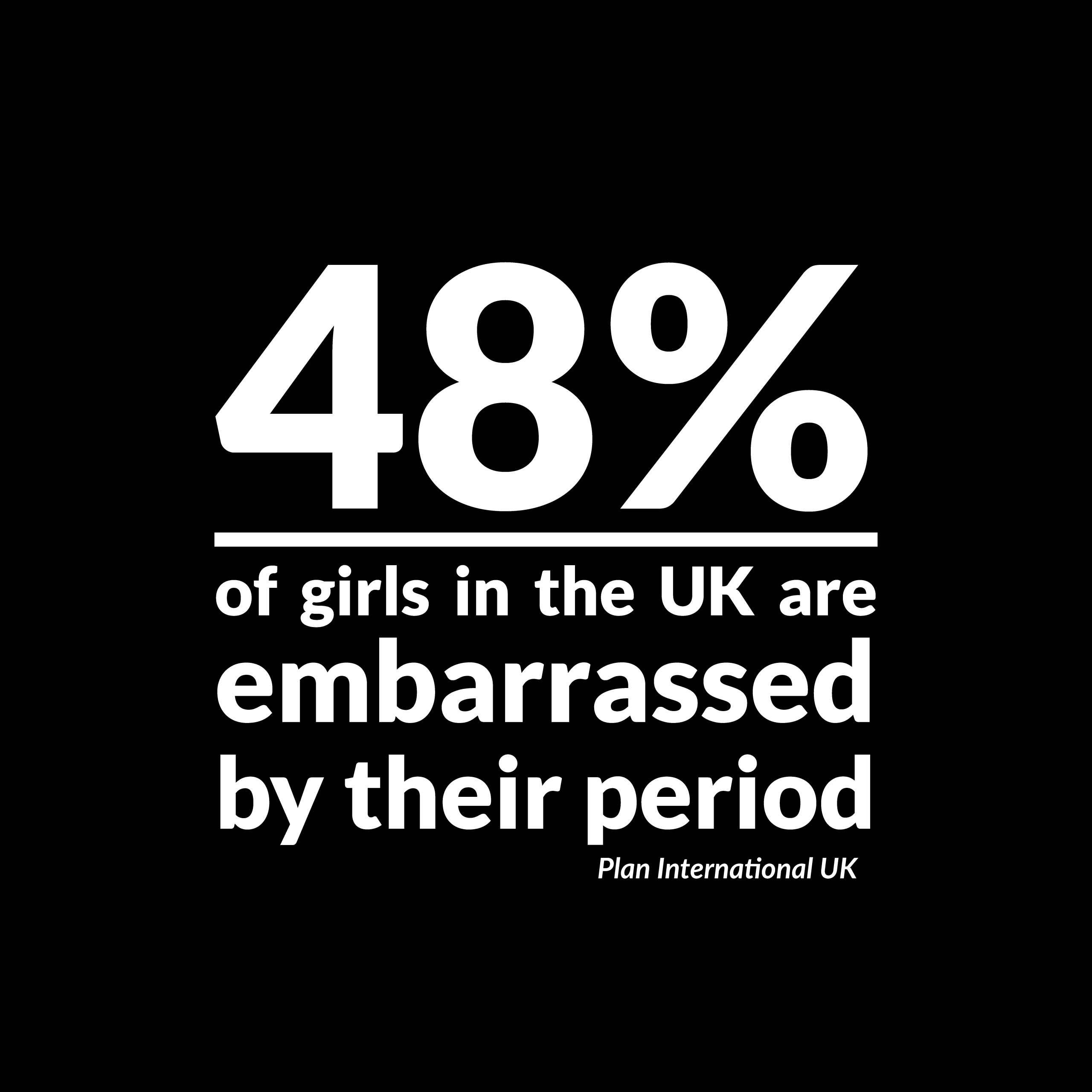

Dahlqvist isn’t alone. Here in the United Kingdom, approximately half of those who menstruate are embarrassed by it and nearly three quarters don’t like buying period products as a result. In addition to that, only one in five young girls and women feel comfortable talking to a teacher, tutor or boss about their period.

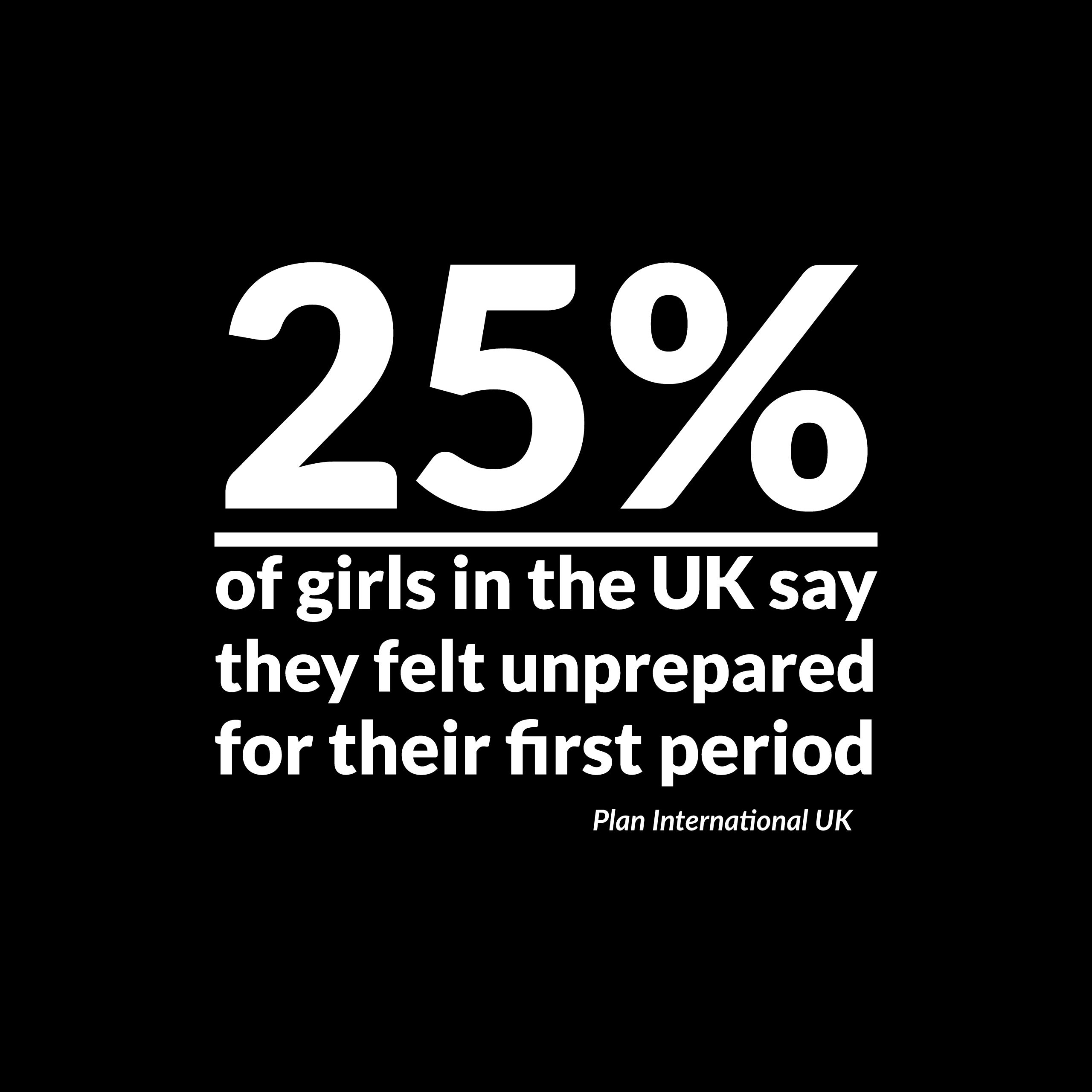

What this does, however, is perpetuate a problem that’s already here. Further statistics in the 2017 report claim that ten percent of girls are unable to afford period products and that even more have had to improvise as a result of ‘affordability issues.’

When tens of thousands of girls are forgoing the use of period products because they cannot afford them, our collective silence about periods is detrimental. Until we start having open conversations about the natural bodily function, many of those who menstruate will continue to suffer.

But this is a problem that’s only grown during the pandemic. An updated report by Plan International UK highlighted that, during the first Covid lockdown, almost a third of all girls struggled to afford period products.

“Lockdown has exacerbated the already prevalent problem of period poverty in the UK... As we look to an uncertain future, many more families will face tough financial choices, and more young women than ever are likely to face issues affording the products they need. We must commit to ensuring they are supported with free access to products, receive timely education on periods and feel able to talk about the issues they face without fear of shame or stigma.”

Before the pandemic, in January 2020, the government pledged to put free period products in all educational settings and hospitals. By March, schools and colleges were closed, and hospitals were largely off limits to anyone without Covid.

Tina Leslie, founder of Leeds-based period charity Freedom4Girls, expressed concern to us about the lack of uptake of free period products by schools and colleges across the UK as a result of lack of awareness of the campaign. This, Tina fears, might lead to the government scrapping the plan.

“I think there’s only been a 40-50% uptake in schools,” Tina told us, as a result of the scheme being “opt-in, rather than opt-out.” Because of this, Tina believes “a lot of schools probably didn’t know about it or were too busy doing other stuff [to sign up].”

It’s evident that when you scratch the surface, the problem is much wider than a small group of people being unable to afford period products. This is an issue that affects, and has affected, hundreds of thousands of girls and women in the UK. Lockdowns have simply made the matter worse.

Much of it comes down to education, or lack thereof. A survey recently conducted by The Sex Education Forum found that a quarter of all girls experience their first period before learning about it in schools.

They say, “the usual age for periods to start is between the ages of 10 and 15, with an average age of 12, but a significant minority will start before the age of 9," and therefore, should begin learning about periods before that age.

Tina says that when setting up Freedom4Girls, she interviewed a number of girls in 2017 as part of an information gathering process to see how bad this problem really was in the UK. One girl in particular sticks in her mind.

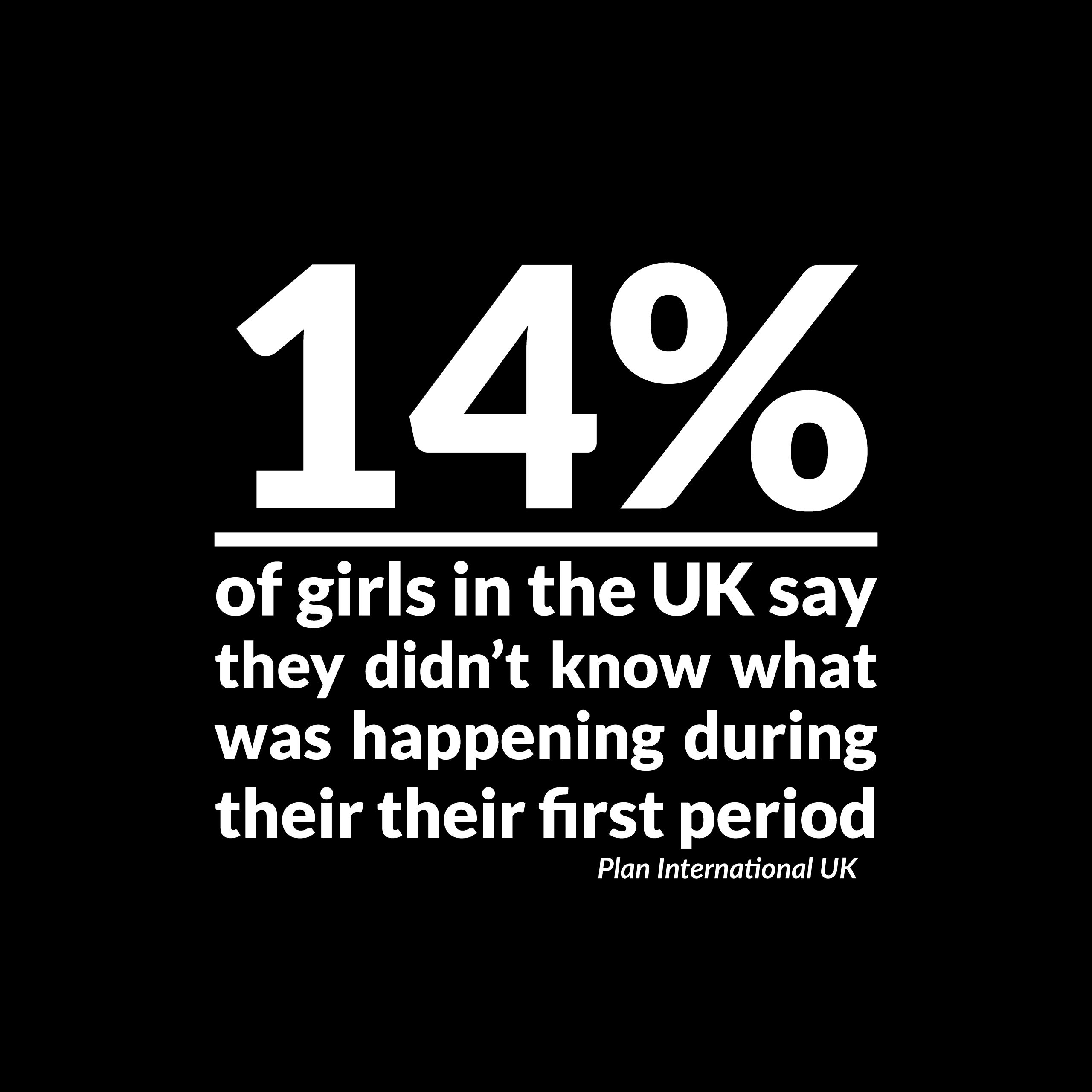

“When we were interviewing these girls in 2017, one of them said they’d had a period for two years and didn’t know what it was,” she explained, highlighting the real lack of knowledge about basic bodily functions right here in our country, "she just managed it for two years without knowing what it was.”

This all comes down to a lack of education. Those at Freedom4Girls, along with other charities across the UK, are offering to go into schools and teach children about periods. Tina says that teachers simply "don't like" doing it.

But how does a country that's placed in the 'top ten educational systems in the world' rely on charities to deliver such vital education to generations of school children?

The longer we stay silent and shy away from periods, the longer it will be until girls stop using newspaper, leaves and socks as period products. The longer it will be until women stop hiding their tampons and putting on a brave face to mask excruciating period pains. The longer it will be until we have a fairer society.

Sally's Story

I’m a teacher in a primary school, teaching early year kids. For me, period poverty is far more than being unable to afford tampons and pads.

I see myself as being in quite a lucky position where I’ve never been unable to afford these products, but like many women, still suffer the consequences of a poorly educated society.

One day in class, I remember I was teaching a group of 30 kids division. It was a warm, muggy summers morning. I’ve always had quite bad period pains and often use a hot water bottle to soothe it. But that day, in the middle of class, I couldn’t do anything.

"It was like someone was slowly stabbing my lower tummy with a hundred knives."

I have found myself in tears before because of the pain. It can be excruciating.

On this one particular morning, I had to leave the class after handing out worksheets to the students. I went to the headteacher’s office to say I needed to go home, even for a couple of hours. I couldn’t think straight, and the heat didn’t help.

It was one of the most awkward and difficult conversations I’ve ever had. Trying to convince a man almost three times my age that I can’t work because my stomach cramps were too painful was impossible. He just didn’t understand it.

Walking back to my classroom in tears, I took some deep breaths and hoped the pain might subdue. I’d taken all of the painkillers I could. Yet still, it was unbearable.

Over lunchtime, the pain got worse. It usually hurts but that day was unforgettable. It was like someone was slowly stabbing my lower tummy with a hundred knives. My back was breaking, and it hurt to stand. It made me feel sick.

"There’s a drought of education in this country about periods."

It got progressively worse. The knives got sharper. My back pain grew more unbearable.

The next thing I remember is waking up in my classroom with two paramedics stood over me. I felt so stupid. My own body had betrayed me and I hadn’t had the strength to carry on. I hadn’t had the strength to plead with my boss that I needed to go home. But I shouldn’t have had to.

Period poverty, for me, is about lack of education. I couldn’t afford to leave work that day, which meant putting up with these pains. Yes, that is part of period poverty too, but if my boss was educated, if the other teachers were educated enough, they’d have spotted the signs and sent me home hours before I passed out.

There’s a drought in education in this country about periods. I know I’m not the only one who’s been through this. I’m just lucky I was in a safe place when I did faint.

There are many women and girls in a much worse position that I am who could’ve ended up in a really terrible situation. Education is important. We need to educate everybody about periods. Maybe then, we can build a more equitable society.

“We always know that someone’s started their period because the toilet paper goes missing,” one school told Freedom4Girls.

In the 21st century, no-one who menstruates should be forced to use newspaper, socks or toilet paper as a substitute for tampons and pads. And those that can afford period products shouldn’t have to hide them up their sleeve on the way to the toilet.

We shouldn’t live in a world where charities are having to go into schools in order to teach children about periods because teachers “don’t like” doing it.

How are we supposed to combat period poverty, if we don’t even talk about periods? If we collectively continue to shy away from the conversation?

We might not be able to rid the country of period poverty overnight, but we can make the country a fairer place to live.

Educate yourself about menstruation. Be curious. And help break the stigma. Tackle the taboo by joining the conversation today.