Is immersive journalism the next big thing in story telling or just another technological fad?

You open your eyes and you’re in the middle of a war zone. Life is moving on as normal somewhat peacefully, with a young girl singing in her native language until suddenly a bomb goes off. Panic sets in all around you as smoke fills your vision and shouting is heard. Then just as quickly as the madness set in around you, you’re back in the comfort of your everyday life.

In another setting, you’re stuck in a prison cell with only the sound of an inmate’s voice to be heard, his words filling up the walls as he recalls his time inside. You feel trapped with nowhere to go until you take off the headset and you’re back to reality.

You can experience the above scenarios first-hand without having to leave the comfort of your home, thanks to the growing world of immersive journalism. With the rise of video and social media, providing news is an ever-evolving challenge that journalists must keep adapting to in order to keep the audience engaged. While print media has slowly been declining in sales over the past decade according to Statista.com, technology has become an everyday part of the average person's life. Instead of reading a newspaper, consumers are watching live news on their smartphones or reading articles on their tablets. But what’s next? Some suggest that Computer-generated virtual reality (CG-VR) and 360 videos may be the next big thing. This is due to the way Virtual reality (VR) places you in a setting you may never find yourself in again. However, like any new technology, questions and worries are raised revolving around its cost, accessibility and impact on viewers.

Nonny de la Pena, often referred to as the ‘godmother of VR’, showcased her piece ‘Hunger in LA’ at the Sundance film festival in 2012. In this VR experience, the viewer is introduced to a line of people waiting for a food bank in downtown LA, with real audio recorded from the scene playing in the background. You can hear the frustration of the crowd as people shout about others blocking up the queue and shoving. Suddenly a member of the line drops on the floor in diabetic shock. The viewer can walk around and see the commotion of the public, while not being able to touch or help those in distress. While her underfunded project was difficult to make at first, it truly started the revolution of VR journalism.

Photo via TED.com

360 Video

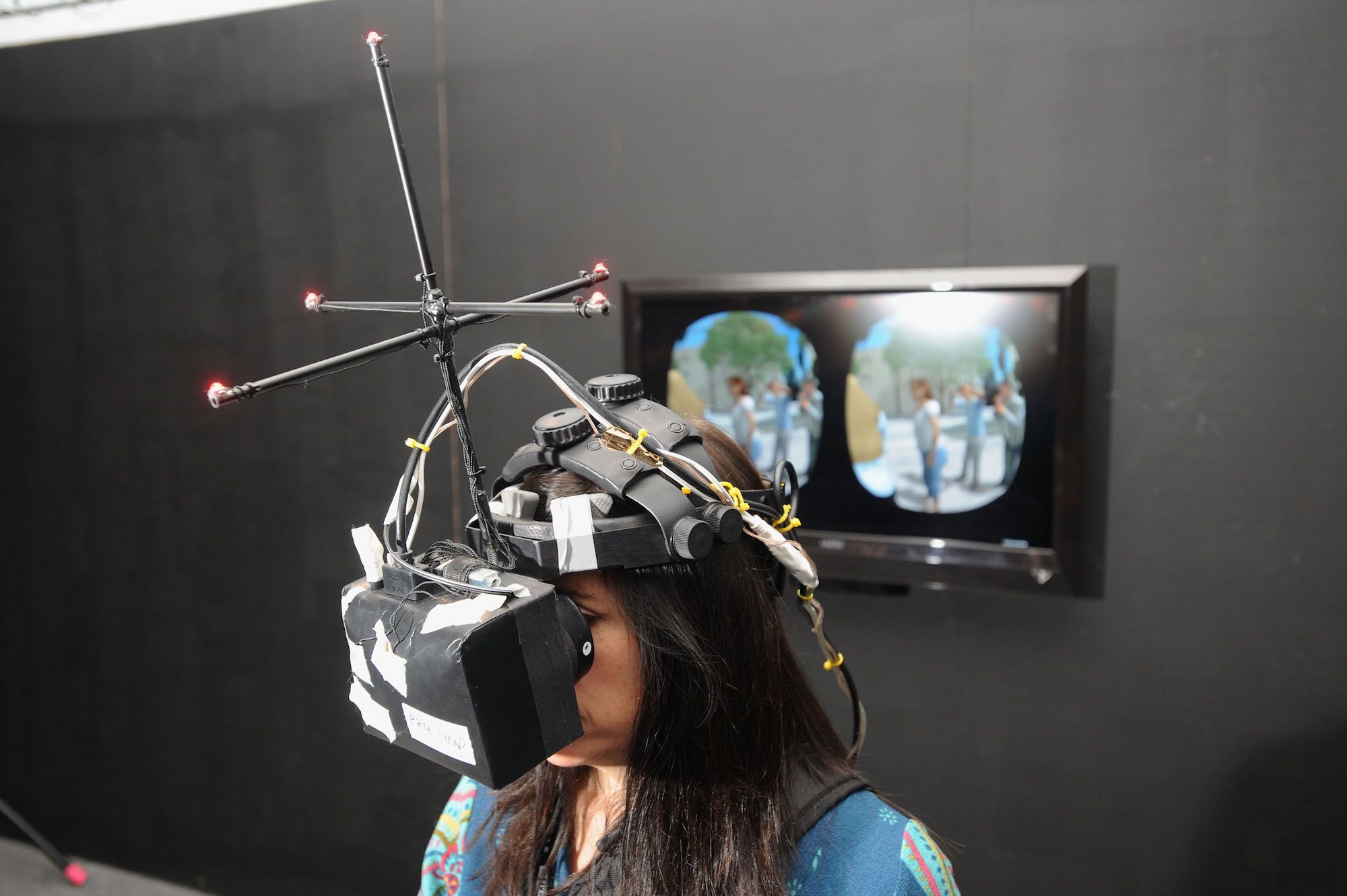

Alina Mikhaleva showing SXSW attendees a VR project at the 2017 festival by Medium.com

Alina Mikhaleva showing SXSW attendees a VR project at the 2017 festival by Medium.com

Audra D.S. Burch and Veda Shastri reviewing a draft of the VR documentary by Tim Chaffee

Audra D.S. Burch and Veda Shastri reviewing a draft of the VR documentary by Tim Chaffee

While there are debates over whether or not 360 video could be classed as VR, it is clearly a method that can be used to create immersive journalism. 360 videos are most often shot with a static camera that films its complete surroundings, or multiple cameras are stitched together in editing software, giving the same effect. This allows the viewer to watch what goes on around them, however, it doesn’t give them the freedom to explore the environment in the direction that they want. The static placement of the video often means the storyline needs to be shot around the camera and brought to the viewer, as they can’t walk around to discover it themselves. The Displaced, a 360 video created by The New York Times is a great example of how to do immersive journalism well, even with the restrictions 360 video can have. By using text and narration alongside the video, it always keeps the viewer interested and looking around to take in every aspect of the scene. Some journalists often make the mistake of only having one focal spot in their piece, which takes away from the point of immersive journalism. The audience wants the freedom to look where they want to look, while still being entertained throughout, which is why journalists need to make sure the entire surrounding adds to the story and engages the viewer.

While 360 video has a more immersive feel than traditional journalism, it comes with a lot of limitations. If the camera is moved in 360 videos, this can create a seasick like effect on the viewer, causing them to feel nauseous, so it is important to keep the camera static although it can restrict the story you are able to tell. In addition, due to the camera capturing its entire surrounding, it becomes difficult to edit out objects you no longer want in the shot, especially in comparison to the ease of editing a normal image or video. This can become an issue when trying to tell a specific story, as there may be aspects that impact the narrative you’re trying to portray that can’t be edited out. However, when documenting a war zone, for example, it is important to include everything that is happening, even if it contradicts the narrative, as journalists owe it to their audience to give them the full real story. Finally, as the viewer decides which part of the video they are focusing on, strong storytelling needs to be used to portray your point and draw the viewer to look at what you want them to look at. The video must be even more engaging than normal video as there is more for your viewer to see which may distract from the storyline you are attempting to portray.

Another example of a 360 video journalistic piece is ‘Remembering Emmett Till’, again by The New York Times, which breaks some of the usual rules when it comes to this medium, but overall creates a very impactful piece. Although moving the camera is usually not suggested, the creators open the piece with a drone flying over Mississippi, although the main focus is on the narration playing over the top. The use of old newspaper clipping, television interviews and imagery from 1955 helps to tell the story of Till, who was lynched at age 14 after being accused of offending a white woman in a store. The use of 360 video in the telling of this narrative helps the viewer explore where this young boy lived and sadly died, with the help of narration and text on the screen always keeping the viewer hooked. While the environment shown on the screen doesn’t seem like much, with the added narration and text, it creates an impactful piece about a horrifying tragedy.

Although there are negatives to 360 videos, they are relatively easy to create as well as not being too costly, with only a GoPro or special 360 camera needed and some extensive editing time. This means media outlets can use this device to tell emotive stories while only needing intermediate editing skills and a small budget. In addition, this media format is the most accessible form of immersive journalism due to 360 videos being available to watch on smartphones and hosted on websites such as Facebook and YouTube.

The Displaced by The New York Times

The Displaced by The New York Times

Journalism 360 Challenge

The Journalism 360 Challenge is a project meant to encourage journalists to try this immersive medium and has rewarded those who create interesting or ground-breaking immersive journalistic pieces. Alex Furman, a winner of the Journalism 360 Challenge, created the project ‘Aftermath VR’, which used a mixture of photogrammetry and 360 videos to show the Euromaidan revolution in Kyiv, Ukraine. He created an app which helped to capture and recreate three-dimensional displays of news events, which he then narrated over the top and added real archive footage of the event to.

Aftermath VR is an immersive VR experience about the most tragic day of the Euromaidan Revolution. We are recreating Instytutska street in downtown Kyiv that became the center of confrontation on February 20, 2014. pic.twitter.com/52it7VJgc0

— Aftermath VR: Euromaidan (@aftermathvr) March 14, 2018

Computer Generated Virtual Reality

Computer generated virtual reality (CG-VR) can be used in journalism to create an immersive story for the viewer to explore at their own pace, in a completely computer-generated environment. CG-VR is most similar to VR games, in which the environment the player can see is completely fabricated by an engine. CG-VR is usually created in a computer game engine such as Unity, in order to shape the virtual world around the viewer. This type of immersive journalism has a greater effect on the viewer as they are completely immersed in the virtual world around them and can control which parts of the story they are close to. While the story unfolds around them, they can choose which areas to view and how to react to the unfolding events, which allows for a deeper feeling of immersion which 360 videos can’t provide just yet.

While the CG-VR pieces are completely computer generated, which often include real sound from the environment they are recreating, there are also creators who use real video from the scene, such as Project Syria which portrays a young girl singing just as a bomb goes off. However, the mix of real-life footage with computer-generated people or environments may take the viewer out of the immersion. Especially due to the often low quality of the graphics, although they have improved over the past few years. Investments in the technology have been made, especially with the rise of VR in the gaming world, and it is becoming a more accepted medium in which to tell a story in journalism.

However, just like 360 videos, CG-VR comes with some flaws such as the level of skill and knowledge it takes to create news stories in this format. For those journalists who are unversed with coding or using an engine like Unity, creating CG-VR may not be achievable without having to hire others who understand the mechanics behind the technology. This was made apparent to Nonny de la Pena while creating 'Hunger in LA', as she was unfamiliar with this medium and somewhat underfunded. While her final piece may not have been highly realistic to look at, the message it told and the use of real-life audio helped to make viewers more immersed and emphatic to the real people in this situation. New advancements in the technology such as WebXR API are making VR more accessible for beginners, but at the moment there are no solutions for those who don’t know how to code. This means 360 videos may be the best option for journalists looking to create immersive stories, at least until there are easier ways to create CG-VR.

Nonny de la Peña, creator of the VR documentary Hunger in Los Angeles, at the 2012 Sundance Film Festival by Fred Hayes/Getty Images

Nonny de la Peña, creator of the VR documentary Hunger in Los Angeles, at the 2012 Sundance Film Festival by Fred Hayes/Getty Images

Zach Wise by Twitter.com

Zach Wise by Twitter.com

Zach Wise

Slightly different from CG-VR and 360 videos, in 2005 Zach Wise used pano heads to take 20 images which he then stitched together to create a 360 image of New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina. This innovative piece gave Wise the opportunity to produce story-telling tools for The New York Times, including more 360-images. Wise went on to win the Journalism 360 challenge for creating a tool that makes shooting 360 pieces easier for journalists, truly working to make this medium more accessible for everyone. While 360 video and CG-VR will most likely be more important in the future of immersive journalism, 360 imagery and people like Zach Wise have helped paved the way for this technology. Although 360 imagery was difficult in 2005, it is now something that can be made on smartphones, which also emphasises how in another 10-15 years, it may be a lot easier to create immersive journalism for the everyday person.

We just officially launched Scene VR in the @knightlab! Just in time for the @Journalism_360 Unconference You can make slideshows of your phone panoramas and/or 360 images and embed them anywhere. https://t.co/hYHdPEmiu9 #Journalism360

— Zach Wise (@zlwise) July 23, 2018

Drawbacks, ethical implications and limitations

Just like any form of new media, immersive journalism raises a lot of ethical questions such as the reliability of the content shown, the long-term effects these stories may have on the viewer and the entertainment value it may have.

Long Term Effects

Due to the recent advancements in technology, it is unknown what long-term effect it may have on viewers, especially children. Being dropped into a such a realistic war zone could impact some users more deeply than others and it has been suggested that people may experience PTSD or other mental health issues after viewing some of the content shown in VR. While this level of immersion may help aid in creating an experience that encourages viewers to have empathy towards people in these war-torn countries, it may do damage to some who place themselves too deeply in the augmented reality. Philosophy professors Thomas Metzinger and Michael Madary published a paper in 2016 titled ‘Real Virtuality: A Code of Ethical Conduct’ which claimed that VR is a ‘powerful form of both mental and behavioural manipulation’. This supports the theory that the power of VR may be too much for some people, especially those who may find it difficult to differentiate from reality and the VR world. While these effects have not been fully measured yet, if immersive journalism continues to become more popular, it will most likely become a large topic of discussion for scholars.

News or Entertainment?

With CG-VR mostly being used in gaming, it may be difficult for a viewer to perceive the content they are viewing as a journalistic piece, instead of another form of entertainment. This would almost fetishize the content being shown and not evoke the empathy desired from the viewer. It can be argued this is similar to traditional media’s use of poverty as entertainment for viewers, more commonly referred to as ‘poverty porn’. A large argument which surrounds poverty porn is how instead of making viewers feel empathic towards the subjects, they see their struggles and stories as a form of entertainment instead of an impactful piece. Subjects are often portrayed as victims and creators often take their vulnerability and package it for consumption, often portraying negative and harmful stereotypes, purely to humour an audience. This could become a big issue for immersive journalism, but on a much bigger scale as due to the impact, VR emotes. It is important for journalists to display content respectfully while still provoking empathy from the audience.

The 'Real' in Reality

Just with any form of media, the truth is something that could become twisted by journalists and even more so due to the computer-generated factors of immersive journalism. Fake news and trolls have taken over the internet in the past few years, and while it has become easier to spot the lies told in these articles for most people, due to the immersion felt while watching VR, it may make it harder to differentiate between a real story or a false one. Many find it important to let the viewer know which aspects of the piece are real and what has been created to add to the storyline. Traditional media has seen a lot of manipulation to favour whichever political, religious, commercial or governmental body funds it, which could easily be continued onto this new form of journalism. This means stories, surroundings and even dialogue could be manipulated to suit whichever group has funded the project, so viewers should be ready to question everything that is presented to them, just as any other media format. It has been suggested that new rules, similar to the ones that are already enforced on journalists, are set for VR journalism, as with the new format comes new issues that need to be avoided. Media theorists such as Ethan Zuckerman and Jaron Lanier have called for a code of ethics to be created for VR journalists, in order to protect the public from intaking false narratives.

Accessibility and cost

The viewers can't afford to view it yet

The whole purpose of journalism is to inform the public on matters they would otherwise not know about. This can not be achieved if the public has no way to access the story, which is a common issue with immersive journalism. Although 360 videos can be watched on the average smartphone or computer screen, CG-VR uses more advanced and expensive equipment which isn’t very accessible or affordable for the average consumer just yet. Oculus, who is a leading company in VR, created the ‘Oculus Rift’ which was bought for $2 billion by Facebook. The VR headset is on sale for around £349 currently, which may be unattainable for most people, especially when there isn’t a large repertoire of VR content available as of yet. While immersive journalism may be more impactful than traditional media, its inaccessibility means there is only a small number of people who can be reached via this medium. The New York Times attempted to resolve this problem by teaming up with Google and sending out over 1 million cardboard headsets to their subscribers, for users to watch 360 videos with their smartphones. This helped gain attention to their 360-video channel and gave their audience a chance to introduce to this up and coming medium.

The Oculus Rift by Oculu

The Oculus Rift by Oculu

In addition to the cost of consuming immersive journalism, the actual desire to watch these sorts of stories may be the downfall of the new medium. While the public may sit down to watch an hour of news on the television or read news articles on their phones for a few minutes throughout the day, plugging into a headset to watch these hard-hitting stories while fully immersed may not be so popular. A lot of consumers watch or read stories passively, which is not possible with immersive journalism which puts the story all around you. This is another way in which 360 videos may have the edge over CG-VR, as 360 allows the option for users to simply move their phone around, or drag their finger on the video without actually having to use a headset.

Luckily, a study has shown that viewing immersive content via a headset or simply a monitor still makes the content more interesting to viewers than traditional written journalism, so although 360 video has some drawbacks and isn’t as immersive as VR, it still is a better option for journalists who want to engage the public.

The journalists can't afford to make it yet

As the technology to produce immersive journalism is new, the cost compared to traditional forms of media may be too expensive for the everyday journalist to use. While 360 cameras are becoming more affordable, such as the Insta360 ONE X which retails around £400, CG-VR is vastly more expensive and requires a certain degree of skill surrounding the technology. Paired with the fact consumers may not even be able to experience this kind of story, it raises the question ‘what is the point of investing so much into a product most viewers won’t even be able to watch?’. However, without the pioneers of this technology, there would be no room for improvement and the equipment would never be more common among consumers and developers. While at the moment, the use of CG-VR is costly for the people making it, hopefully in the future when it becomes more common the price will lower and it’ll be seen as a more common form of journalism, just as smartphones became a part of everyday life. Again, this is where 360 video overtakes CG-VR as it is relatively easy and affordable to make. Normal journalists can make it with only a small amount of experience in the area and budget.

Impact on Empathy

A big defence made against the flaws that come with immersive journalism is the way viewers reportedly feel more emphatic towards the subject in these pieces, compared to traditional journalism. Being completely surrounded, often including the real-life audio, helps the viewer put themselves in the shoes of those around them. It visualises the horrors of a war zone or the isolation of a solitary cell, without putting the viewer in danger. However, this does raise the question ‘Does VR diminish the actual experience of those living in these conditions?’. Although the answer to this may be yes, the positive effects from immersive journalism may outweigh the negatives, as it’s proving an eye-opening chance for people to walk in someone else’s shoes. It is also a lot more impactful than traditional journalism and makes viewers more likely to sign petitions.

RYOT, a news organisation dedicated to creating stories that inspire viewers to take action such as donating money to a cause, created their first virtual piece, 6x9. As shown above, 6x9 includes a virtual cell with narration from a real inmate who has experienced solitary confinement. Molly DeWolf Swenson, the co-founder of RYOT, stated that people connected so well with the piece as they know they are ‘going to be able to take off [the] headset and return to a normal life, but that’s not the case for 80,000 Americans who are in solitary confinement today.’. This is most likely why everyone who tried the experience then went on to sign a petition for ACLU to stop using solidarity confident cells, which Swenson said was ‘basically a 100% conversion rate’.

While immersive journalism is proven to evoke more empathy from viewers than traditional media, it’s the journalist’s job to provide their audience with interesting and true stories. The latter is extremely important as it could make or break VR. If the market is over-saturated with pieces that are riddled with fake news or incorrect facts, viewers will be less interested in believing all the VR content out there and see these journalistic pieces as games. Plus, just as any form of new technology, as more people invest into virtual reality, it will become more affordable to the public and creators. While the technology advancements are already being made, it’s vital that journalists use new storytelling methods to keep the audience engaged, in order to bring immersive journalism into the mainstream. While CG-VR stories may be unrealistic for most media outlets to produce, 360 videos which can be accessed via smartphones, tablets or computers are the perfect gateway to get consumers interested in immersive journalism. Just as any form of journalism, ethical rules must be made to ensure the audience is getting a true story and are not being misled in any way.

While it is unknown whether immersive journalism will become the newest medium to take over the world of news, it is clearly picking up popularity and those who are lucky enough to experience it will never forget the story they saw first-hand. While there are a vast amount of ethical implications and limitations, if ethics are made to monitor what journalists are putting in these pieces, the empathic response from viewers will help bring this medium to the mainstream. Hopefully one day in the future, immersive journalism will be the main way to access new stories, giving everyone the chance to plug in and be completely absorbed into a once in a lifetime story.

Photo via Wikimedia Commons