Credibility in UK Journalism.

How much can we trust the press?

Journalism in any country plays a vital role. To inform, enlighten and give a voice to millions of people. Giving them the opportunity to be included in a wider debate ranging from anything from social issues to politics. The ability to trust your journalists is therefore also crucial, if we can’t trust our journalists then who can we expect to provide us with factual information to broaden our knowledge of the contemporary world? As time goes on it seems that trust and journalism are two words which seem to almost contradict each other in the eyes of the UK public.

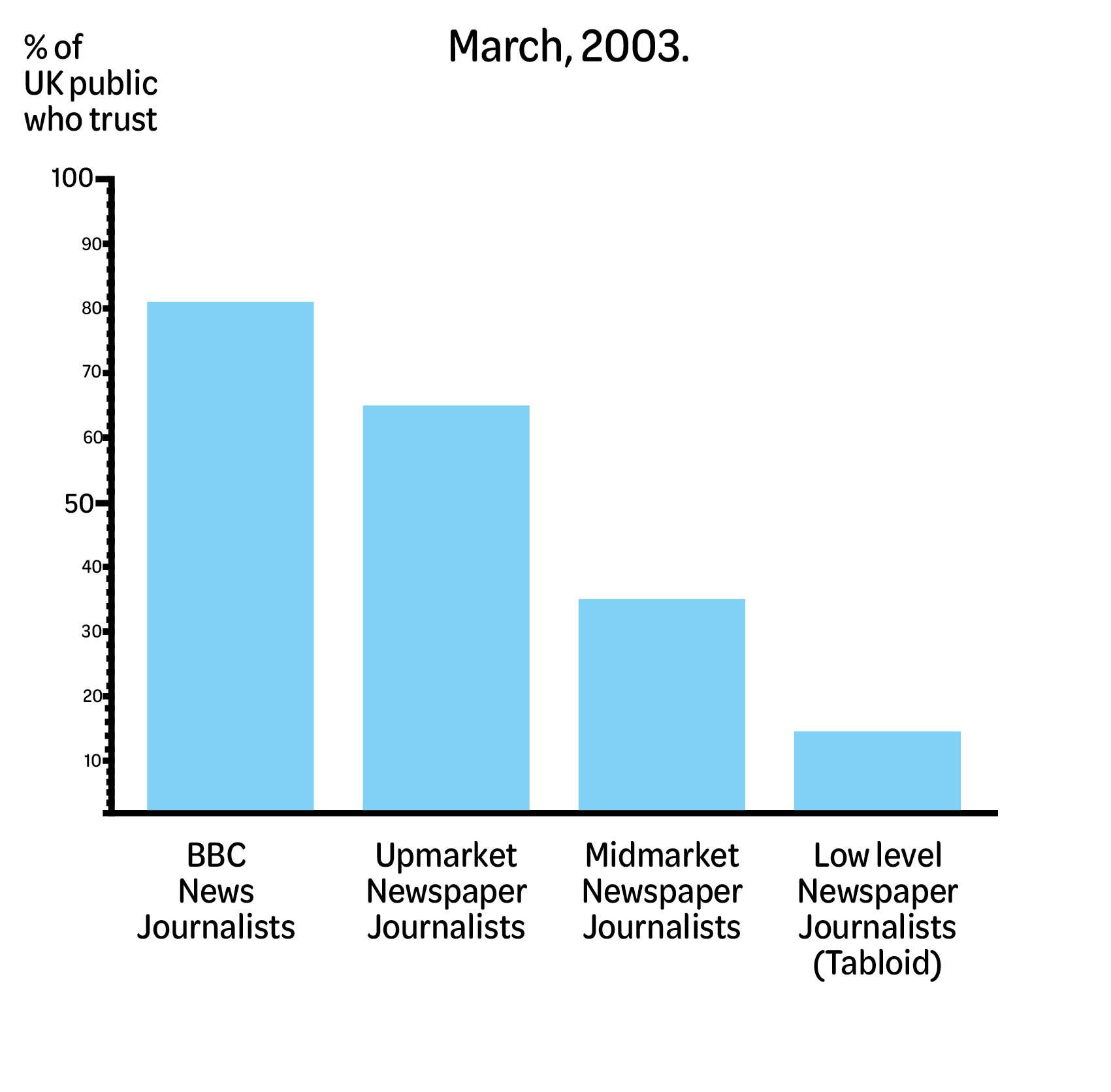

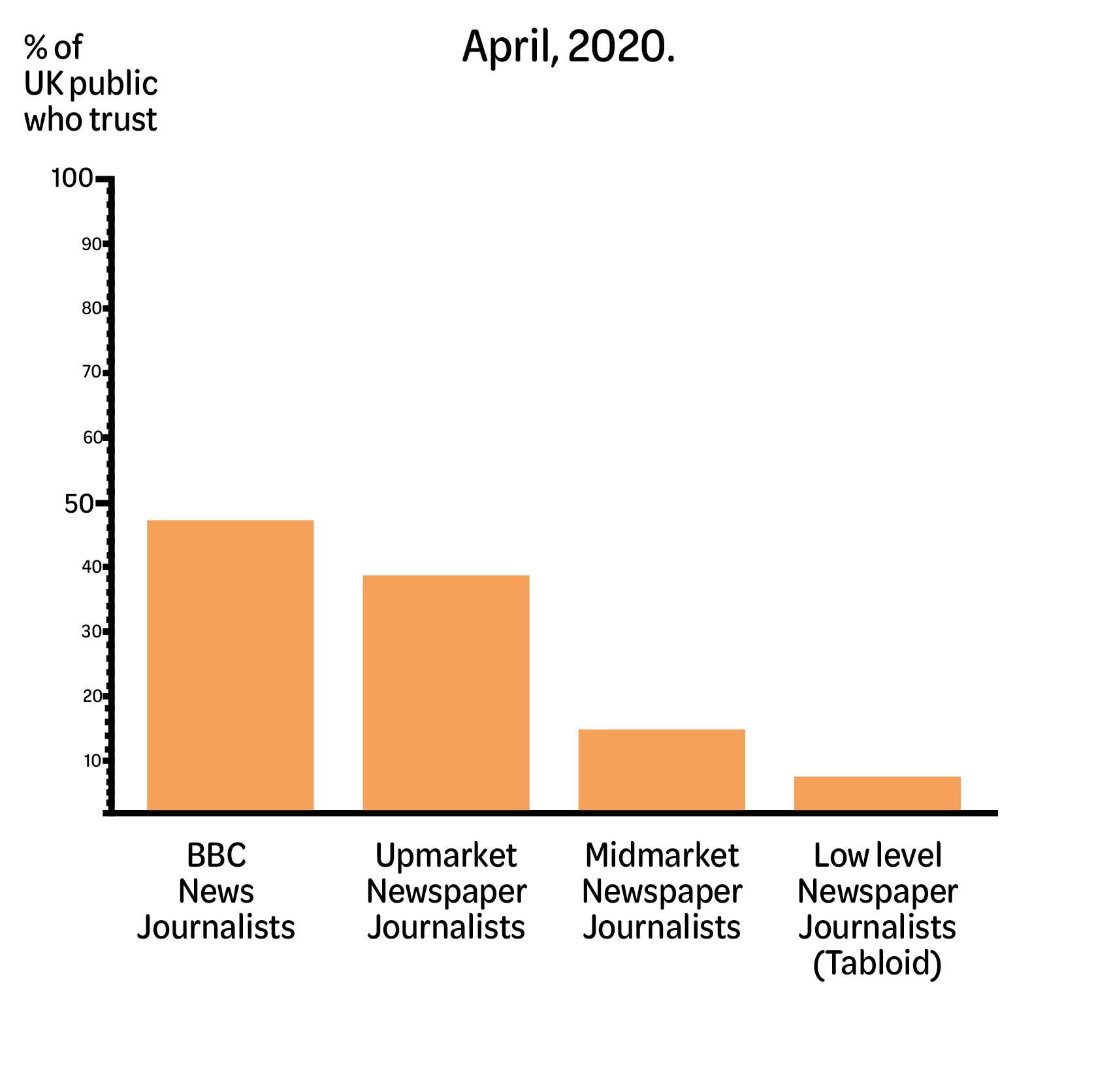

Over the past 20 years, a poll by YouGov has asked the UK public whether they trust different groups to ‘tell the truth’ – the groups included within the poll are that of doctors, teachers, police officers and estate agents amongst a plethora of others, including Journalists.

From the pollsters results it’s safe to say Journalists have fared pretty badly, with negative correlations across the board from the sub-sections that YouGov has divided the industry into. Mainstream Media such as the BBC clocked in with 47% of people trusting them to tell the truth in April of 2020. Whereas Journalists on ‘mid-market’ and red-top tabloid newspapers were only scraping round by the 10% mark.

A Journalists credibility has often been referred to as the butt of a joke, and people are very quick to express their thoughts on their credibility record – often being called out for mincing words to aspire to an agenda and contributing misinformed information stricken with bias. But what really is causing this trend of the UK population losing trust in it’s journalists and news organizations, and what are the contributing factors?

Journalism in a nut-shell, is simply the method of gathering, assembling and presenting news and information to an audience. This somewhat loose definition means that it’s disputable where Journalism in the UK originated from. William Caxton introduced the first English printing press in 1476, by the early 16th century the first newspapers began to fumble around England, however due to a largely illiterate population people were still l reliant on town criers to deliver news to them. Despite this the print press did begin to eventually take off, and we’re now seeing centuries old newspapers still circulating around our country.

Since then News and Journalism has evolved and moulded with a continuously changing world. Town criers have since been abandoned and made way for Broadsheet and Tabloid Newspapers, allowing space for TV Journalism and subsequently adapting to the wormhole that is the Internet. Journalism has become a strong component in aiding the formation of National Identity and providing information to populations which breathes life into our democracies. This is what makes trust in journalism so imperative, admittedly a certain level of distrust is a healthy characteristic of a democratic system, but a very low level of trust and believability can endanger the functioning of journalism and possibly consequently our country, as a whole.

A free press is what is necessary for Journalism to contribute to a democratic society. Meaning that the Government in any particular country has no stake in what the press in said country has to write. The Press Freedom Index is an annual ranking system which has been assembled by Reporters Without Borders, judging the countries on their press freedom records from the previous year. At one extreme end of the stick you have countries such as North Korea & Turkmenistan whose governments control all media and only few internet users are able to access a highly censored version of the internet. At the other end you have countries to the like of Norway, Finland & Denmark who’s governments play no part in their press and pride themselves in their democracy and freedom of expression. The UK lies somewhere in between, far closer to the last-mentioned, although remains to slip down the rankings from previous years. Threats made to reporters in Northern Ireland played a large role in this, the death of journalist Lyra McKee who reported on the unrest in Derry and after police inappropriately obtained warrants to search the homes of reporters Trevor Birney and Barry McCaffrey made Reporters Without Borders call for the UK to launch a national committee for the safety of it’s journalists.

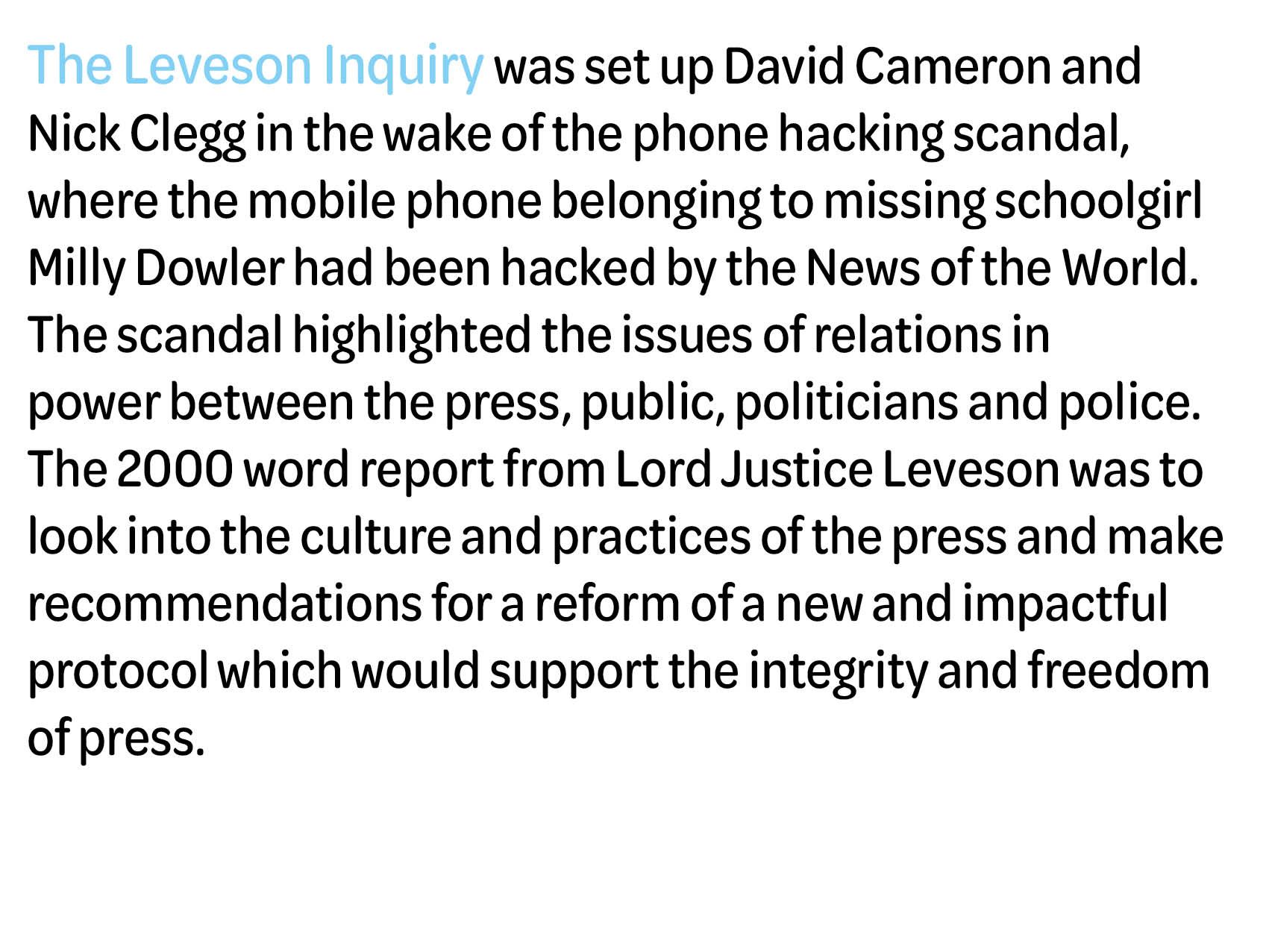

However, many people favour the argument that the UK actually has no press freedom whatsoever. With the majority of UK press under a very concentrated ownership structure, with around six billionaire tycoons owning the majority of the mainstream media. It’s to many peoples belief that the agenda from the source at the top of the pyramid trickles into and consciously and subconsciously floods the newsroom with the same ideology. Rupert Murdoch, Australian born and now US residing owner of Global Media Conglomerate, News Corporation has been made accountable for claims like these before. News Corporation is the home to famous British newspapers The Times, The Sunday Times, as well as famed most read British tabloid The Sun and also long demised News of the World - in which phone hacking controversy sparked The Leveson Inquiry.

Former editor of The Sun, David Yelland, inferred in an interview with the Evening Standard that Rupert Murdoch was not necessarily the boss where influence and agenda went unnoticed.

"All Murdoch editors, what they do is this: they go on a journey where they end up agreeing with everything Rupert says but you don't admit to yourself that you're being influenced. Most Murdoch editors wake up in the morning, switch on the radio, hear that something has happened and think: what would Rupert think about this? It's like a mantra inside your head, it's like a prism. You look at the world through Rupert's eyes."

This isn’t the first inkling that Murdoch may overstep his mark as the simple owner of The Sun and it’s sister publications either, perhaps exercising his influence slightly more than appropriate. Andrew Neil, who edited The Suns sister publication the Sunday Times between 1998 and 1994, spoke to the Lords communications committee in 2008 and described Rupert Murdoch’s position at the Sun as the “unnamed editor-in-chief”. Disclosing how the editor of the Sun would get almost daily phone calls from Murdoch himself. Neil went further onto depict how Murdoch’s influence would not be under mimed, outlining how it would be inconceivable for the Sun to endorse one political party for an election, if Murdoch’s view was to vote for the other.

Even on the other side of the world in Australia, former prime minister Kevin Rudd referred to Murdoch’s Journalists as “Journalistic Agents” who are “tools and a political operation with a fixed ideological and in some cases commercial agenda.” Rudd has since launched a petition to the federal parliament in Australia, calling for a Royal commission into News Corps overwhelming control of print media (where Murdoch owns around 70% of newspaper circulation) in the interest of democracy. So far the petition has amassed more than 280,000 signatures.

News at its core should be neutral, objective and unbiased. When journalists are reporting, naturally they should be telling both sides to a story in a weighted approach. Allowing the audience to make up their own mind on the subject they are disclosing. Personal attitude towards facts, whether it be doubt or ambiguity, should be avoided. However, like David Yelland, Andrew Neil and Kevin Rudd state, when writers and editors at The Sun look at the world through Rupert Murdoch’s eyes, with a fixed ideological view, and are frequently answering phone calls from him, it makes the objectivity of the paper understandably unclear.

Murdoch hasn’t been short of controversy in the past, alongside the phone hacking, rubbing shoulders with politicians and controversial tweets it’s no wonder that content provided in his publications cast a shadow of doubt over the heads of it’s readers and it’s further audience, therefore hindering the trust of the public. Its unfair to associate the goings on at News Corporation to other publications, especially that of a disreputable tabloid, but it only takes the minority to give the majority a bad name.

Rupert Murdoch. Photo: Bloomberg via Getty Images

Rupert Murdoch. Photo: Bloomberg via Getty Images

Left to Right: David Yelland, Andrew Neil, Kevin Rudd.

Left to Right: David Yelland, Andrew Neil, Kevin Rudd.

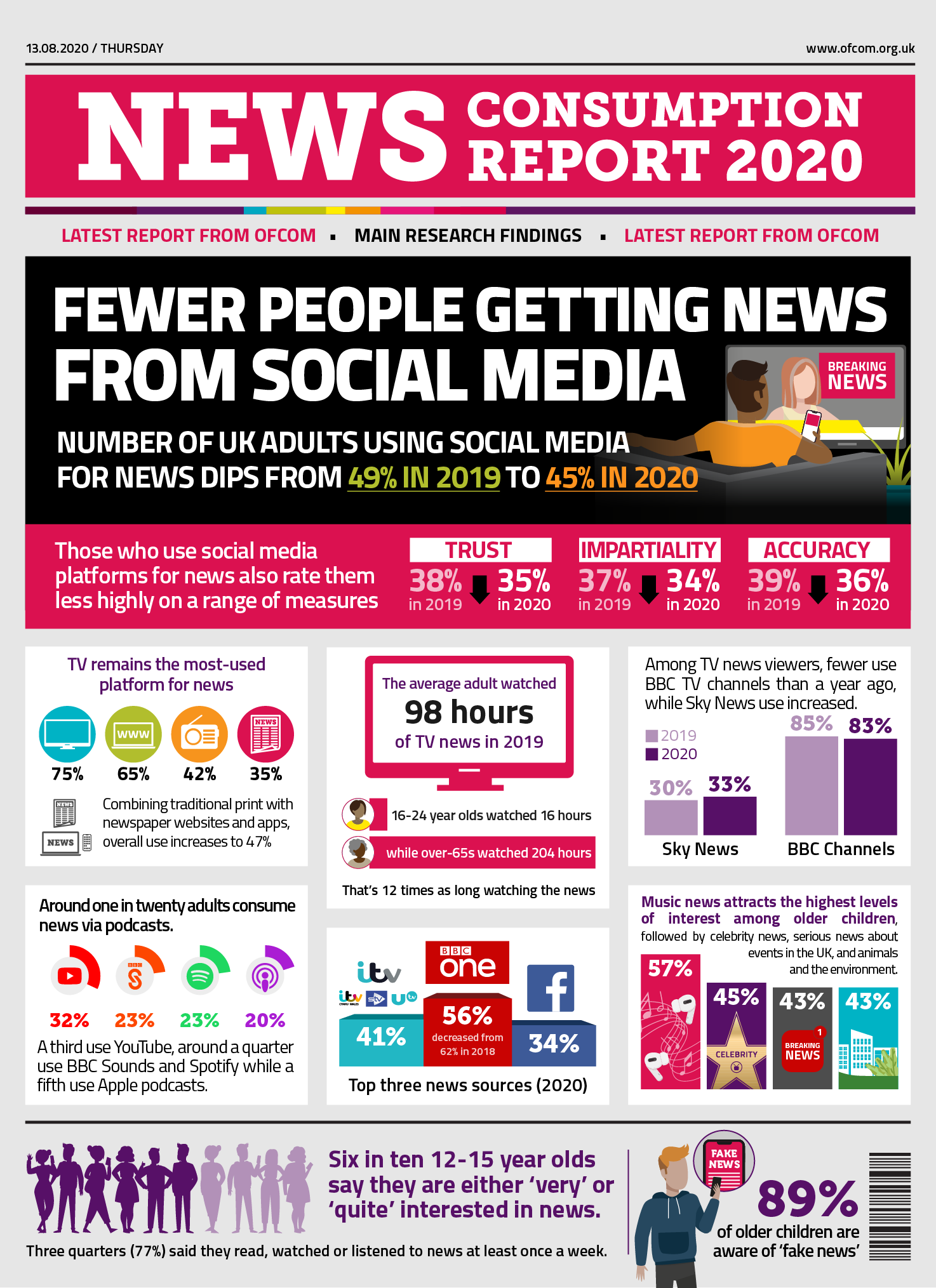

Ofcom's News Consumption Report 2020.

Ofcom's News Consumption Report 2020.

Others argue that the crumbling credibility of journalists doesn’t lie with the influence of those who own the publications, but the everchanging landscape in which journalism now finds itself in. The world in which people consume and obtain their journalism has changed drastically, so much so that the definition of a journalist has practically been redefined since that of the old broadcast and publishing models. The print press made way for the television and now they are both still making way for the internet and all of the avenues which come as a result of it.

Looking at results from the 2020 news consumption report in the UK from Ofcom, TV still remains the most used platform for news with 75% of people watching it. However the internet is not far behind with 65% of people using the platform to get their news fix. Compare this to only 35% of people now reading newspapers for their news and you can clearly see what direction the world of news is sliding in, considering that the internet has only been widely accessible for the last 30 years.

The world of journalism has already been inherently competitive, but now that news is shifting towards the realm of being online it seems that the dog-eat-dog nature of the industry will only advance. Nowadays the audience is exposed to an overwhelming amount of information at their fingertips. So much so that to make sure your content is seen, publications need to make sure that their content catches the eyes of its readers. Through this medium what has been born is now a competition for clicks. Many publications also now depend on selling advertisements as their means of revenue. The need for traffic through the publications accompanying websites and other social media platforms only adds to the dynamic of the sensationalized media environment. Striking headlines are now the norm to bait the audience into clicking onto stories, however the price to pay for this new era of click bait journalism is that behind the headlines is often underdeveloped and inaccurate stories.

Alex Green, Reporter at PlymouthLive.

Alex Green, Reporter at PlymouthLive.

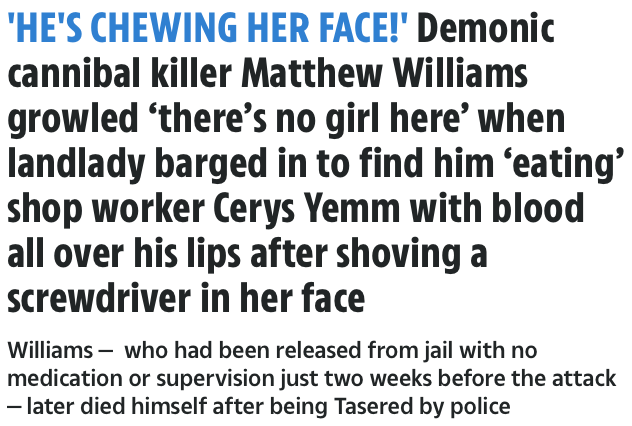

Headline from the Sun which was later revealed to be misleading.

Headline from the Sun which was later revealed to be misleading.

Tweet from ex-EDL leader Tommy Robinson in wake of false report from Mail Online.

Tweet from ex-EDL leader Tommy Robinson in wake of false report from Mail Online.

Alex Green has been a reporter at PlymouthLive for the last year and agrees with the point of view that the unfathomable volume of information on the internet is partly to blame for damaging Journalists credibility. “Anyone can set up an account or website and start writing their version of the news, and there actually is an abundance of false information out there, which can look on the surface, remarkably similar to accurate, factual news.” Alex is correct, nowadays, you no longer need to have an advanced computer skillset to curate your own website. Anyone fairly competent with a computer can now setup their own website in half a day, even from their own mobile phone. This medium now opens up doors for anybody, with their own agenda to publish online, depict it as “news,” even though the information could be false, misconstrued, inaccurate or completely fabricated.

“Fake News is everywhere.” Alex continues. “I feel that when there is so much of it out there, it makes it extremely difficult, if not impossible to decipher between what’s truthful and accurate and what’s not – and therefore the natural response is to lose trust in the journalist.” The term coined by Donald Trump during his campaign to become President of the United States and then famously throughout his presidency was used as an insult against any news agency and publication which slandered him. Behind the somewhat disputed allegations from Trump however, Fake News is a very real phenomenon. In the UK fake news even dates back to the mid 1700s, where printers printed false news that King George II was ill in an attempt to destabilize the monarchy. In a more modern world however Fake News continues to intervene it’s way into society, in some cases from some fairly reputable publications and sources. Fake News in the UK over the years has ranged from the arguably harmless, to the outright shocking and panic provoking.

In 2017, The Sun reported on the tragic murder of a woman. The Sun disclosed that the murder committed by a man with mental health issues was “cannibalistic” detailing how the man was found with blood on his lips after ingesting the woman. The report was ruled as false however after a later press council ruling noted that after an inquest into the tragedy showed no evidence of the woman being devoured. On the 24th of November of the same year the Mail Online also reported that a lorry had ploughed into pedestrians on Oxford Street in London by using a 10 day old tweet as a source, also detailing that gunshots had been heard at the scene. The headline prompted a convinced response by the public, even causing ex-EDL leader Tommy Robinson to tweet following the proposed terror incident. The false story sparked panic in the area, and once revealed there was no evidence of shots being fired or casualties, outrage online on social media. Even the BBC, home to the UKs most trustworthy journalists according to YouGov’s poll has had its fair share of fake news scrutiny after wrongly claiming that 100,000 universal credit claimants would lose their benefits over Christmas, forcing the British Broadcasting Corporation to issue an apology.

Although there’s no outright or admitted explanation for these reports which have been categorised as “Fake News. One such explanation may be down to what Journalists refer to as the rush to publish. In the past there was an unavoidable delay for publications when publishing news stories, however now, the world works in a much faster way. The audience expects news almost instantaneously whereas journalists never have been one for a slow news day. Journalists want to be the first to get the scoop on a story, and the first to publish it. Winning this contest means that the news outlet and the journalist get the credit for breaking the news. This means that most of time, in newsrooms around the world, Journalists are under a considerable amount of pressure to get the story, construct it and present it ready for the audience. This tenacious attempt to get information out as quickly as possible means that the door left open for errors to wonder in gets wider.

Errors in news can vary. Simple grammatical errors, missing punctuation and spelling mistakes can crop up every now and then, but occasionally an error can pose the risk of having much more catastrophic consequences. Markets are volatile, credibility walks upon tight ropes and the news organization can face legal liability. Hence why whilst journalists are trying to beat the rush to publish, they must ensure the story they are reporting on has been ran through and fact checked with a fine tooth comb. Just because a source has been referenced doesn’t mean that its true.

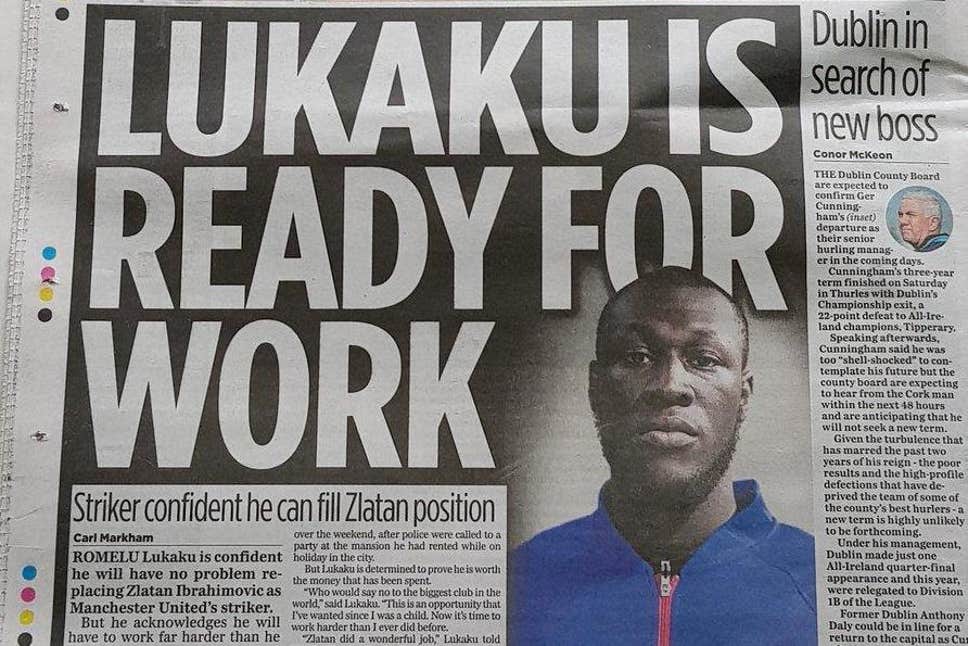

Evening Heralds story on Lukaku using Stormzy's photo.

Evening Heralds story on Lukaku using Stormzy's photo.

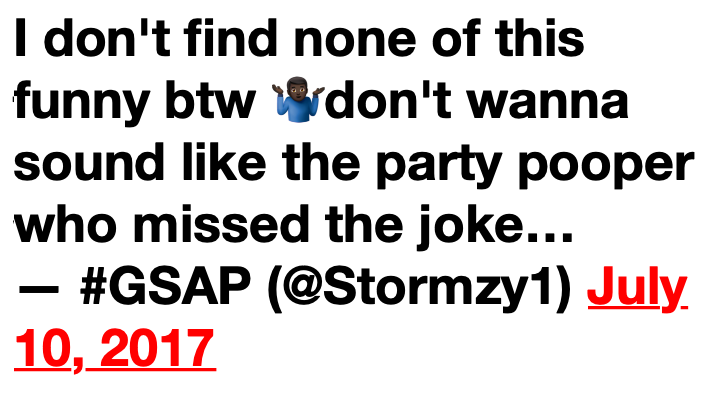

One classic example of an error which most likely came from beating this rush to publish was courtesy of the Irish paper, Evening Herald. In 2017 the paper ran a story based around Belgian footballer, Romelu Lukaku and his move from football clubs Everton to Manchester United. The story ran with the headline “Lukaku is ready for work,” and detailed the promising strikers transfer between Premier League clubs. However the publication sparked controversy when instead of including an image of Lukaku himself, ran with a photo of infamous Croydon rapper Stormzy. This case of mistaken identity ignited mixed reactions, some people found it funny, others, including Stormzy, not so much. It’s easy to view the mistake as extremely careless and to make light of the issue. But when questions of racism begin to be raised, the joke unequivocally turned sour. Even though the error can be rectified promptly, mistaken identity itself can be damaging for a papers reputation. Add the speculation of racism into the mix also, especially when endorsed by a celebrity with influence like Stormzy, and their credibility can be ripped to shreds.

Tweet from Stormzy after the case of mistaken idendity.

Tweet from Stormzy after the case of mistaken idendity.

Alex also believes that another contributing factor to the decline of a journalists credibility is that of social media, predominantly Facebook and the way that it controls the narrative. “If you work for a news organisation, you’ll know how dependent on Facebook a lot of news providers are. The algorithms set out by Facebook make it impossible to reach every reader with every piece – because your news feed will show you what you’ve proven to engage with before,” says Alex. “These algorithms essentially mean that Facebook set the precedent on which kinds of news stories will perform online – and while journalists are still covering the essential every day stories, Facebook doesn’t show its audience anything it thinks won’t get the most engagement – and that’s just arbitrary, so if a story/piece of content is divisive or inflammatory it will do well because lots of people will comment – meaning Facebook’s algorithm will prioritise that, regardless of its accuracy.”

Social Media does have it’s benefits, they act as a gateway and can drive traffic towards publication with search engine optimization. Functions within the websites can allow for open conversation and feedback between journalists and readers and also allow for the readers to get to know the journalist on a more personal level – therefore enjoying the journalists work, not just the work of the publication. However Alex’s statement does hold true. Conforming to the rules of algorithms hinders objectivity. Audiences don’t know what pieces of the puzzle are missing because they’re out of view. Whilst the news corporation has no say whether or not they want to adhere to the algorithm, social media sites are trapping their audience in a filter bubble, which if that bubble were to pop and expose that reader to more information, could challenge and broaden their viewpoints. Journalists should constantly be attempting to do this when delivering news, but becoming slaves to the algorithms does not allow them to, and in today’s climate if journalists and news organizations want to take part in the game, they must play by the rules.

In an ideal field of journalism it would be to look at the points discussed and attempt to avoid them. However the reality is there is no quick fix to the issues discussed. Unfortunately the world we live in isn’t going to change overnight. Rupert Murdoch and his inability to keep his influence within his lane and media empires of a similar variety aren’t going to disappear in the blink of an eye. Mark Zuckerberg isn’t going to abandon his algorithm purely for the sake of journalists. It’s also unlikely that sensationalism and competitive publishing encouraged by investors and advertisers in the pursuit of profits will go anywhere anytime soon. Trust in Journalism is a strange topic really, it seems that when curated in paragraphs like so, there should be no reason to put our trust in their hands. Like previously discussed, we’ve never been at a time in our lives where we’ve had so much information and so many ways of consuming it. In all of the chaos of hearing so many voices at once, it’s important for journalists to be there so we can have an authoritative voice to make sense of it all.

It may so be that Rupert Murdoch and his journalists are only telling one side of a story, and filter bubbles online are telling the other half. But to remain clued up, well informed and equipped with the knowledge to make up your own mind you must always take both into account. Even the journalists and their publications which we trust the most, we must still be sceptical, taking into account those at the other side of the fence and listening to their side of the story. Even when it pains us to do so. To trust our journalists more, we ourselves must take on the role of editor and rule out any unverifiable sources. The fact is, unlike maths, in journalism 2 plus 2 doesn’t always equal 4. Only will we know what the truth is after looking at both standpoints.

Ann Curry is an American Journalist who has been in the profession for over 30 years. She stands by the philosophy of the audience taking on a more sceptical role when consuming journalism, in an effort to revive the relationship of trust between journalists and the audience. She believes that credibility lost may never be credibility regained, but in wake of all that seems to be going wrong in journalism. It seems that particularly in America, the public is now realising how vital journalism is for a democracy. Publications are making a stand in the face of corporate owners, take the Denver Post for example. We’re seeing the audience being increasingly demanding and supporting quality work in the form of subscription based payments. Donating to the committee to protect journalists. Balanced and investigative reporting is making a resurgence, telling all the nuances of the story, allowing for the audience to make more rational judgements. Perhaps this shift in momentum may be something we can see a lot more of in coming years, particularly in the UK and our own publications.