Restoring

Hope

THE FUTURE OF JOURNALISM

The world needs a new story.

"It’s a good time to be a pessimist. ISIS, Crimea, Donetsk, Gaza, Burma, Ebola, school shootings, campus rapes, wife-beating athletes, lethal cops—who can avoid the feeling that things are falling apart."

How did the media coverage on Hurricane Katrina affect the New Orleans community?

This August will mark 14 years following the chaos that Hurricane Katrina caused. Headlines of Anarchy, Chaos and Lawlessness were declared on the front pages of papers across the globe in August 2005. Media coverage of the devastation Hurricane Katrina left in New Orleans (NOLA) came to define a once-thriving city as a city in need, in a spiral of hopelessness.

In the immediate aftermath of Katrina hitting New Orleans, reports described all kinds of horror happening in the city. Stories of snipers firing at innocent people from buildings, bodies piled up in the streets, gangs tormenting people seeking refuge in the Superdome, and sharks in flooded streets. Reports even detailed graphic accounts of children being raped and killed in public spaces. None of these reports were verified or substantiated. Little of it was true.

Remember this after Katrina? The difference between "looting" and "finding" is often black and white pic.twitter.com/nZoaP0KJ2l

— Steadman™ (@AsteadWesley) August 29, 2017

Images of people leaving local retail outlets with electronics dominated television and newspaper coverage around the world. Although, Lieutenant General Russel Honoré, who coordinated the 300 national guardsmen sent in, says in an interview that the majority of looters were trying to find food, water, diapers and medicine. “It was way over-reported. People confused looting with people going into survival mode. It’ll happen to you and I if we were just as isolated.”

Lilly Wokneh, HuffPost's Black Voices Senior Editor referred to the coverage of Hurricane Katrina as “a tale of two cities”, the difference in coverage and language used to refer to white and black victims of the storm was “appalling”. Contrasting captions of nearly identical images of black and white survivors caused outrage. An image of a white survivor was "finding" food while an image of a black survivor was "looting" a store. As Journalist Joshua Adams points out, the racial news framing of Hurricane Katrina illustrates the power of the stories we tell. It shows us how the media choose what voices to amplify and those to omit.

Woman cusses out CNN reporter in Texas:"Y'all trying to interview people during their worst times. Like that's not the smartest thing to do" pic.twitter.com/MbZ3vMLtWs

— JM Rieger (@RiegerReport) August 29, 2017Woman cusses out CNN reporter in Texas:"Y'all trying to interview people during their worst times. Like that's not the smartest thing to do" pic.twitter.com/MbZ3vMLtWs

— JM Rieger (@RiegerReport) August 29, 2017

What is Restorative Narrative?

We’ve all seen first-hand the power of the media to affect change, good and bad.

“Stories have a transformative power to allow us to see the world in a different way than we do if we just encounter if on our own. Stories are an entry point to understanding a different experience of the world.”

In recent years, technology has become a key focus within the media landscape. Although this is important, we also need to draw our attention to the types of stories we tell. As Jeff Sonderman points out, "what if newsrooms were to put as much emphasis on recovery and restoration as they did on tragedy and devastation?" Nationally-recognised storytelling genre Restorative Narrative refers to journalism or storytelling that highlights the assets of a particular individual or community instead of the deficits and shortcomings. Images & Voices of Hope (ivoh) are a non-profit media group who coined the term “Restorative Narrative” in 2013 to describe "a genre of stories that show how people and communities are making a meaningful progression from a place of despair to a place of resilience." Mallary Tenore describes restorative narrative as intending to "cover the story beyond the immediacy of the breaking news, and in doing so, to help individuals and communities move forward in the wake of large-impact events." As Tenore puts it "Now more so than ever, it seems, the world needs stories like this."

With the emergence of Restorative Narrative, controversy and scepticism of positive news came with it. Many say that positive news stories are merely fluff, accompanied with the old adage “positive news doesn’t sell.” As Mallary Tenore refers to them, "these aren’t happy-go-lucky fluff pieces." They are rooted in often painful reality, “positive in the sense that they focus on themes such as growth and renewal — themes that, at some point in our lives, we can all relate to."

Naturally, there are inherent risks in this type of storytelling. Some examples…

"Not all stories about a tragedy can be turned into restorative narratives. Time is a critical component. You couldn’t write a restorative narrative about a person in the immediate aftermath of a tragedy/difficult time because it would be inauthentic; the person wouldn’t have had time to heal yet. Sometimes these stories take months, and even years, to report." - Managing Director of ivoh, Mallary Tenore

"False positives. Restorative narrative does not mean that the positive elements of a story should be accepted without question. Scepticism is called for as much in restorative narrative as it is in other forms of nonfiction storytelling." - Journalist, Steve Myers

"Journalists aren’t trained for this kind of storytelling. The majority of journalists were trained to report with a focus on a problem." - Journalist, Steve Myers. Such an approach often fails to acknowledge, let alone explore, multiple perspectives of a story. “The way to get the world we want is not to troubleshoot the world we have but it’s to envision the world we’re moving towards.” – Judy Rodgers, ivoh founder.

Restorative Narrative for Katrina Survivors

In 2012, a project called The Resilience in Survivors of Katrina (“RISK”) published a study that researched the effect that Hurricane Katrina had on women’s happiness over a four year period. The results were encouraging and surprising, showing that only one year later, almost 89% of women remained “somewhat happy” or “very happy”, although a drop in happiness on average, the study showed how people are more resilient than they given them credit for. ivoh points out that this study highlights "the importance in supporting the community fabric of populations that are vulnerable."

What opportunities are there for the media to craft Restorative Narratives?

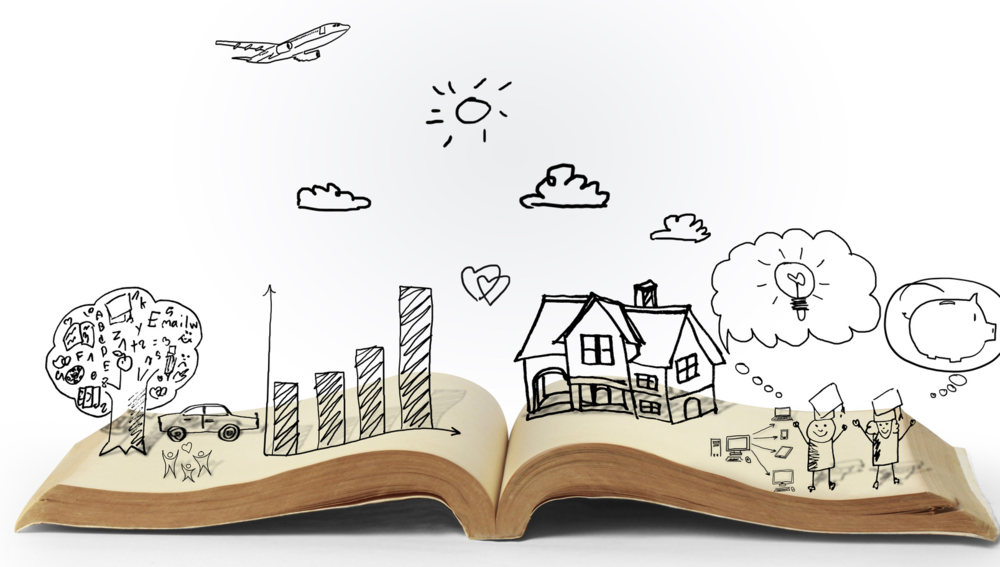

The chart below by the former head of digital engagement for the Guardian, Meg Pickard, illustrates the gaps and opportunities that exist in media today.

This highlights the untapped potential for both the healing that journalists can play in the restoration of communities, and the opportunity to create in-roads for communities to be involved in the process. The Geraldine R. Dodge Foundation make the distinction between “building with communities” instead of “building for communities.”

Building for the community puts people at the end of the process, whereas building with community puts them at the start.

Lauren Ellen McCann offers this description:

“’With’ implies togetherness, whereas ‘for’ centres on the experience of individuals in a relationship, with one unit acting on behalf of or doing something to another. When we talk about building with our communities we have to talk about power, and about new systems of power where we gain strength and sustainability from connections to each other not transactions between each other.”

McCann argues that “‘For’ is the thorn in the paw of the ‘civic’ movement today. We espouse to build new, collaborative systems, new technologies, new relationships […] but we do so wielding old systems of power.” This seems to suggest that journalism doesn’t just report on what happens in communities but also contributes to how they transform.

The aim being to create more in-roads for community participation and give people more power to contribute to local journalism, although this process is complex and time intensive, it is vital to the sustainability of journalism. Journalist, Josh Stearns explains that "regardless of your business model, having your community deeply invested in what you do, is key to the long term sustainability of your work. Building with community is also about building more resilient organisations, rooted in relationships that can help both challenge and support you." Not only does this add accountability and value to journalism, but as Anna-Catherine Brigida says, "this type of journalism represents the largest part of the media market, or what Ohio University journalism professor Bill Reader refers to as the 'bottom of the iceberg.'"

Who is already doing this?

Non-profit organisation, ivoh, aims to make media agents of positive change. Studies suggest their work to develop this genre is having an impact on journalists worldwide.

"Storytellers have to be discerning observers of life in our times. They have to be able to see beneath surface glamour and trauma to the deep resilience within communities."

The media’s often-immediate response to the aftermath of tragedy comes in the form of “what happened” stories and can leave us feeling like the world is a hopeless place. After a while, these stories an “inaccurate” inherent truth. Alongside the sometimes insensitive approach that reporters take. Political scientist John Mueller points out, “in most years bee stings, deer collisions, ignition of nightwear, and other mundane accidents kill more Americans than terrorist attacks.” As Tenore puts it, "the persistent focus on death and devastation ignores the fact that there are stories of resilience and recovery to be told."

Appalachia: Trump country?

"We had always felt there was a lack of responsible coverage of the region, and then the election gave us a platform and an urgency, because everyone was looking at us." says Maryanne Reed, Dean of the Reed College of Media.

After the 2016 election in the U.S, reporters from national media scrambled into Appalachia with a frame already in mind to report on “the heart of trump country” and urban-rural conflict. Poor, white and angry people trump-supporters live in trailer parks and work as coal miners. This became popular belief, albeit a misrepresentation and narrow perspective of a diverse region. The lack of authentic, holistic coverage of Appalachia is the result of a post-industrial economy and following the elections, it became a place where parachuting journalists would report on the “real America”, seeking to discover Trump’s appeal. In response to the mass sensationalised coverage, 100 Days in Appalachia was founded. A collective of local journalists formed a news collaborative organisation which originally started out with the intention of covering Trump’s first 100 days in office but ended up continuing the project. Their aim was to write stories that would counter the national narrative of widely held beliefs on Appalachia, challenging preconceived notions and provide readers with a diverse range of perspectives on the region. The project could be attributed to the genre of Restorative Narrative due to the fact that reporters didn’t sugar coat issues and highlighted the positives and restoration in the region in an honest way.

How do the media frame stories?

To frame is to present a story from a specific perspective. They are usually crafted to divert focus to particular aspects of a story, and not to others. When a journalist tells a story, it is filtered through their individual and collective understanding – whether conscious, or not. How we frame stories has the power to shape global perceptions.

It’s assumed that news acts like a mirror, just “reporting” facts and events without bias. Of course, news cannot be completely objective and unbiased. However, after analysing the coverage of Hurricane Katrina, more and more questions were raised around how the media chose to frame the tragedy. What lens were the national media filtering information through? Did the coverage reflect perspectives with underlying assumptions and beliefs? Was this lens deciding who did and didn’t deserve empathy, or who was and wasn’t a victim?

It is generally accepted that negative frames are more likely to grab people’s attention. There may be some truth to this perception but the important thing to note here is the effect it has on the public, and journalists. “Depending on what gets highlighted and what gets overlooked—and how stories are framed—the media can accelerate social progress or do just the opposite,” says the Solutions Journalism Network, another organisation who aims to change the kinds of stories the media report on. Messages that induce fear lead the audience to overestimate the likelihood of something bad happening to them, although this may heighten their awareness and attention, the fear can immobilise them. In the case of Appalachia, the analysis of coverage shows the disproportionate impact the media had on how perceptions were shaped, and merely contributed the long standing commentary of shaming white Appalachia.

“As a storyteller, I’m drawn to darkness. Restorative Narrative, for me, is about finding the flickers of light in the dark.” – Alex Tizon. I think that this is something a lot of journalists can relate to, journalists are trained (wired) to source stories that are often full of tragedy and darkness. They want to find the problem, expose the problem and hold people accountable. This is a crucial aspect, however, telling restorative narratives is just as important. To see the person or community that is struggling and understand what the struggle is about and along the way, see the remarkable things they do despite that struggle.

"For most folks, no news is good news, for the press, good news is not news.”

Fear conditioning and culture of fear

Decades of headlines that focus on ‘the imminent danger’ of immigrants and terrorists pervade society, and with it, our cultural beliefs. Newsrooms work by a hierarchy of which I’m sure we’ve all heard if it bleeds, it leads. This approach follows two aims. One being to get the viewer’s attention, often referred to as a teaser. The second being to convince them that the solution to removing the perceived fear can be found in the story. The success of this approach lies in the addition of dramatic anecdotes (versus hard evidence), referring to isolated events as trends, selecting what groups of society are dangerous, and fatalistic narrative (replacing optimism.) News sources benefit from and rely on fear due to the fact that when fear is heightened, so are ratings.

This kind of fear-based media has become a part of popular culture, and brings with it storytelling genres of horror, crime and fantasy. It results in a barrage of responses from the body and mind of people exposed to it. Those who consume excessive amounts of news can disassociate from their surroundings and start to believe their world is dangerous, and thus fear it. Often fearing that their communities are unsafe and believing that they are likely to become a victim of a crime.

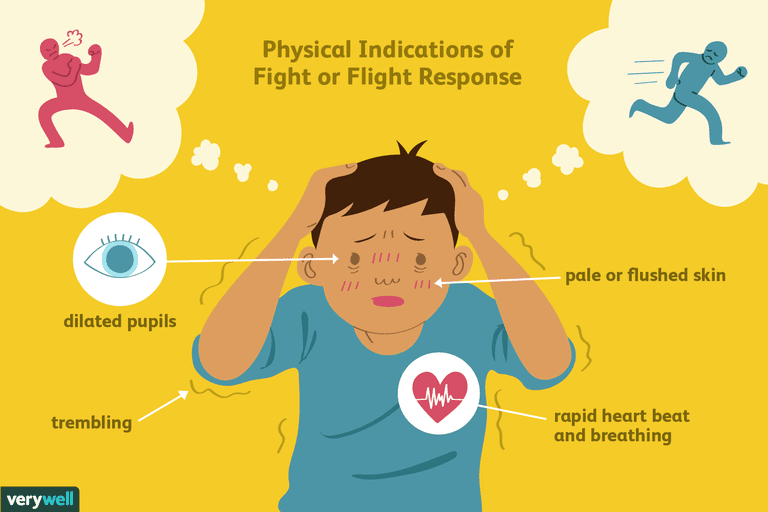

Fight or flight: The bodies protection response to fear

Illustration by Joshua Seong. © Verywell, 2018.

Illustration by Joshua Seong. © Verywell, 2018.

Traumatic coverage can be often be so intense that it leads to symptoms of acute stress disorder—like sleeping problems, anger outbursts, anxiety, panic attacks and even PTSD.

There is a common misconception in the world of media and that is that fear prompts people to take action. When surrounded by multitudes of unresolvable worries, broadcasted in the media, our stress levels rise. As the nervous system recognises a threat and alerts the body to impending danger, it goes into fight or flight mode. This process happens in the HPA axis, which stands for Hypothalamus-Pituarity-Adrenal axis. The trigger response causes our bodies to stay in a state of constant adrenaline, resulting in chronically elevated stress hormones. The HPA axis system is a protection mechanism for handling acute stresses, although it is not designed to be continuously activated. Bruce H. Lipton PhD has found that overstimulation of the stress hormone is "linked to significant damage and long-lasting functional changes in the brain."

"We live in a “Get-set” world and an increasing body of research suggests that our hyper-vigilant lifestyle is severely impacting the health of our bodies."

Daily stresses cause the HPA axis to be constantly activated, preparing our bodies to go into action. When the threat does not elevate causing us to take action, the stress hormones sustain and are not released. Lipton explains in his book Biology of Belief how nearly “every major illness that people acquire has been linked to chronic stress.” A fitting example of the role the media played in the story of the 9/11 tragedy and how they contributed to an increase in stress amongst the population. The media reported a consistent presence of danger following the attack, causing an increase in adrenal signals. Lipton explains how "this shifted the members of the community from a state of growth to a state of protection." When the body becomes chronically stimulated by misperceptions, we can’t distinguish whether the threat is real or imagined. The result of this is the "creation of hardwired, stress-linked pathways between the hippocampus and amygdala that result in a vicious cycle of maintaining a constant fight-or-flight state of mind." This shows how fear does not prompt people to take action, but instead paralyses them from taking any action as they psychologically shut themselves down in a protection response from the perceived threat, thus comprising their bodies health.

Nocebo: The power of negative beliefs

"Your beliefs become your thoughts. Your thoughts become your words. Your words become your actions. Your actions become your habits. Your habits become your values. Your values become your destiny."

Many people are aware of the Placebo effect and the power of positive thinking, yet few have considered the nocebo effect and the role negative thinking can play in your life. The media is filled with hope-deflating stories that, in the words of Mahatma Ghandi, can become your destiny. This means that the long-term effect of constantly consuming negative news can determine your future through programming the subconscious mind. Studies in neuroscience have found that "the conscious mind runs the show, at best, only about 5 percent of the time." Programmes acquired by the subconscious mind dictate 95 percent or more of our life experiences. Lipton explains that "since subconscious programs operate without the necessity of observation or control by the conscious mind, we are completely unaware that our subconscious minds are making our everyday decisions." Lipton's research found that "brain cells can translate the mind’s perceptions of the world into complementary and unique chemical profiles that, when secreted into the blood, control the fate of the body’s 50 trillion cells."

When we change the way we perceive the world, that is, when we “change our beliefs,” we change the blood’s neurochemical composition, which then initiates a complementary change in the body’s cells.

Doctors, parents and teachers can dissolve hope by leading you to believe you are powerless. In this way, the media can too frame stories in a light that leaves an audience feeling hopeless and powerless.

Drip-down effect on health

Negative perceptions can lead to chronic stress that then has a "profound and negative impact on gene function." Findings from studies on mice show that "long-term exposure to stress hormones can leave a lasting mark on the genome" and modulates the behaviour of genes that control mood and behaviour. Studies also show that behavioural epigenetics can carry over to subsequent generations.

“Your belief carries more power than your reality.”

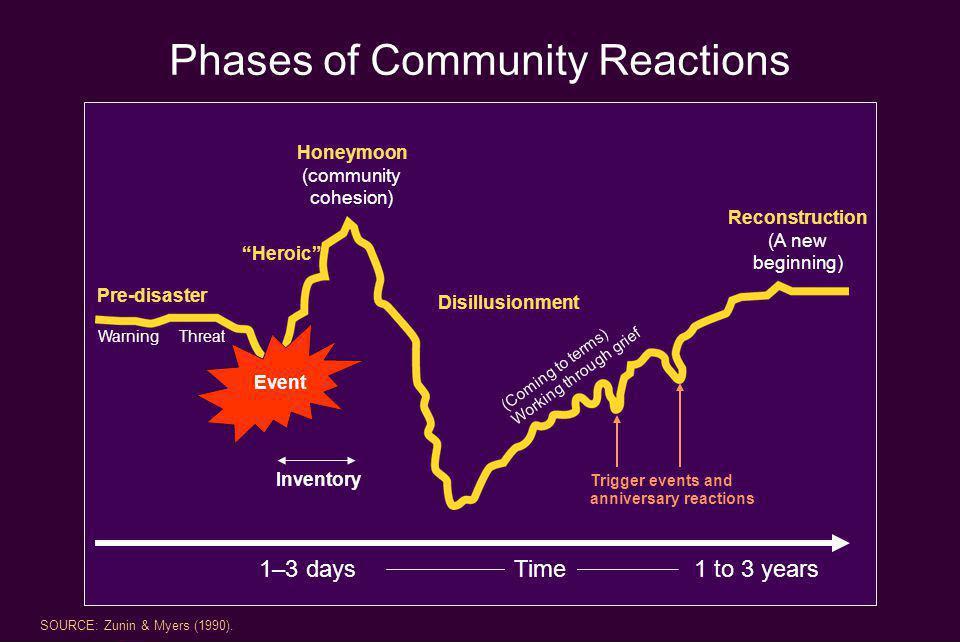

This graph shows what the trajectory is like in dealing with trauma. It’s a reminder that trauma does stay with us for a while.

Broadcasting happiness and positive psychology

"The good news is that bad news can be turned into good news when you change your attitude."

As Mark Rice Oxley from the Guardian says “The good news is people like to read good news.” Research reveals that people want to read and share transformative news. In a study analysing the kinds of content that go viral, researchers Jonah Berger and Katherine Milkman found that “positive content is much more likely to go viral than negative content.”

We are all broadcasters. We are constantly broadcasting information to people, even without words. The messages we choose to broadcast can shape other’s view of the world and how they respond to it.

Dr. Langer’s ‘Counter-clockwise’ study shows how our mental story affects our health. She hypothesised that “the human ageing process is mediated by what we tell ourselves about our life stories.” Her findings successfully proved her hypothesis and showed how we can reverse the ageing process through positive programming. This study shows that simply by changing the way we tell our stories, we can become more fulfilled, healthier and live longer lives.

A 2011 study in social psychology has found that when we see others acting with courage and compassion, we feel uplifted–referred to as ‘moral elevation’. This induces positive emotions, restores faith in humanity and “inspires them to act more altruistically.” Other studies conclude that constructive stories that show how people are handling problems can inspire commitment and action in readers.

“Positivity is the world’s most under-utilised, natural occurring resources available to fuel successes and forward progress.”

Michelle Gielan writes in her book Broadcasting Happiness, about a viewer that wrote in during Happy Week at CBS News, “One viewer from Oklahoma wrote in, and his story still makes me emotional. His home, like many others, was facing foreclosure. He wrote that he had not talked to his brother, who lived a mere 25 miles away, for the past 20 years. They had fought over money and cut off contact. He had recently heard that his brother’s home was facing foreclosure as well, and after seeing the segment on CBS on rethinking financial stresses, he decided to reach out to him. The two men ended up pooling resources to save one of their homes and moved in together. Each was now very happy to not only have a roof over his head but also his estranged brother by his side. This story was one of many that showed how people are propelled to take positive action when they experience even the smallest mindset shifts, and what results is a new reality.”

As Geilan puts it, following this narrative is a "pathway for people to reach a more positive mindset, attain higher levels of optimism and deepen social connections." The world needs more people broadcasting happiness.

Whitman Alabama: A Restorative Narrative

Verse 37 in Scottsboro

Filmmaker, Jennifer Crandall working at AL.com (Alabama public media). Crandall set out to change the stereotypes about Alabama, using Walt Whitman’s transcendent 52 stanza poem ‘song of myself’. She crisscrossed the state of Alabama, asking Alabamians to read a stanza of the poem, to camera. This clip is read by a circuit court judge in drug court in Alabama. Given the mass coverage on the opioid crisis in the U.S., this is a striking treatment of drug addiction. This is verse 37, reading the poem, our circuit court judge, John Graham and Chris freeman. This treatment of the subject as a restorative narrative shines a light on those who have survived drug addiction. Restorative narrative connects us to a wellspring of strength and spiritual power.

What can you do?

Here are some changes that everyone can make to ignite positive change, take steps towards crafting restorative narratives and better serve communities:

For the newsrooms

Bring in outside talent. Simply not having the time is a reality in many newsrooms as journalists often find themselves working the jobs of 3 people. A way to combat this is by bringing in outside talent who have more freedom to experiment with Restorative Narrative.

In-roads for communities. Rebuild the newsroom with community in mind. Create more in-roads for communities to participate in the process before their story becomes a transactional product.

Calm mind traffic. Follow in the footsteps of ivoh and set aside time to clear mind traffic. At ivoh’s Annual Media Summit, they make this a priority. “At the top of every hour, we stop for a minute – even if we’re in the middle of a panel – and music plays. Then we sit for a moment silence. This is supposed to clear the traffic in your mind. A lot of people at the end of the summit say ”wow, that was really helpful” and then aim to build it into their classrooms/newsrooms” – Mallary Tenore

Create space. Make room for work that goes beyond the deadline-driven 24-hour news cycle.

Focus on local. Place more value on your local storytelling rather than national stories.

Push boundaries. Shift the media landscape by pushing the boundaries of what “public media” is supposed to look and sound like.

For the Journalists

Restorative narrative says, “what’s next?”, “what’s possible?”, “How can I work to resolve this issue?” In this way, it has similar characteristics to ‘solutions journalism’, but goes way beyond it. It’s about syncing and grounding yourself deeply into the community that is affected, establishing trust, and saying that “we not only want your story, but we want to honour your story and work with you on it”. It is a relationship between the storytellers and the people in the community.

Get to know them. Reposing is an antidote to rushed reporting, requiring time and patience to get to know a community. "Listen to the sounds and silence, to walk the streets with open hearts and a nonjudgmental gaze, to engage with people who may see you as an outsider." - Mallary Tenore.

Turn sources into storytellers. As mentioned earlier, stories biologically have the power to heal, so allow a space for people to tell their story and have the opportunity to release and heal.

Share information. Keep people informed in the early days of a crisis, do rumour control and let them how they can not only help themselves but the situation. As you found out earlier, this can empower people to take hold of their own stories and affect positive change.

Look for stories of resilience. Following a crisis, revisit communities and ask “what is going on there?” and “how are they recovering?” to craft a story of resilience and show people that there is positive growth. Often, when we say resilience, it seems like a grandiose word but usually small moments of resilience are where the story lies-tell the whole story. Although these stories may take longer to hard, they are well worth it.

Keep in touch. Make an effort to keep in touch with the people you connected with in communities, they will be more likely to contact with you another story in future. You’ll also get a chance to revisit stories and report on the developments, crafting your own restorative narrative.

For the individual

Limit news consumption. As Michelle Gielan explains below, beginnings are so important. Start your morning and bedtime off right–without news.

ADD VIDEO CREDIT.

Find good sources of news. Spend some time searching for news sources that resonate with you and induce a "feel good" state. See the end of this article for recommended sources.

#positivestories. Use this hashtag to search for your morning dose of restorative news.

Let media outlets know when you've enjoyed a restorative narrative piece. To keep journalists writing and newsroom publishing more restorative narrative articles, make sure to let them know when you've enjoyed it.

Broadcast happiness. Go about your day-to-day starting conversations with what Michelle Gielan refers to as a "power lead". Scan your world for something positive and share it. It's that simple.

For the communities

Community-newsroom collaboration. Organise an event for community members and journalists to have an honest discussion.

Empower youth. Encourage the younger people in your community to share their stories.

Take part in the conversation. Communicate, communicate, communicate. Create spaces to meet up with your local community regularly, a safe space where people can go to be heard, and feel seen.

What is the future of Journalism?

David Brookes reminds us what we should be working towards, “We are morally inarticulate. At this point in history, we can’t afford for this to be the case. At some point, there will have to be a new vocabulary and a restored anthropology, emphasising love, friendship, faithfulness, solidarity and neighbourliness that pushes people towards connection rather than distrust.”

"The world needs a new story."

Mallary Tenore reminds us that "Now more than ever, we need stories that give us a window into people and cultures that are different from our own so that we can better understand and appreciate the rich tapestry of cultures far and wide." There are many restorative narratives yet to be told, especially in rural communities where traditional media doesn't tend to reach.

"When you enter a community as a person first and a journalist second, you begin to see it not through the lens of your camera or the quotes in your notebook but through the eyes and ears of the people who live there.” It is important to step back and view media through a wider lens, as it reveals it is "a mix of reporting, anthropology, ethnography, engagement, and art." - Mallary Tenore

Restorative narrative is a people-powered, community-driven process which allows a space for people to shape their own stories whilst establishing a sense of ownership over the process, in turn creating new systems of power.

Remember, your beliefs shape your reality.

Sources of good news: