Who's Opening Doors in the UK

Rabar's Story

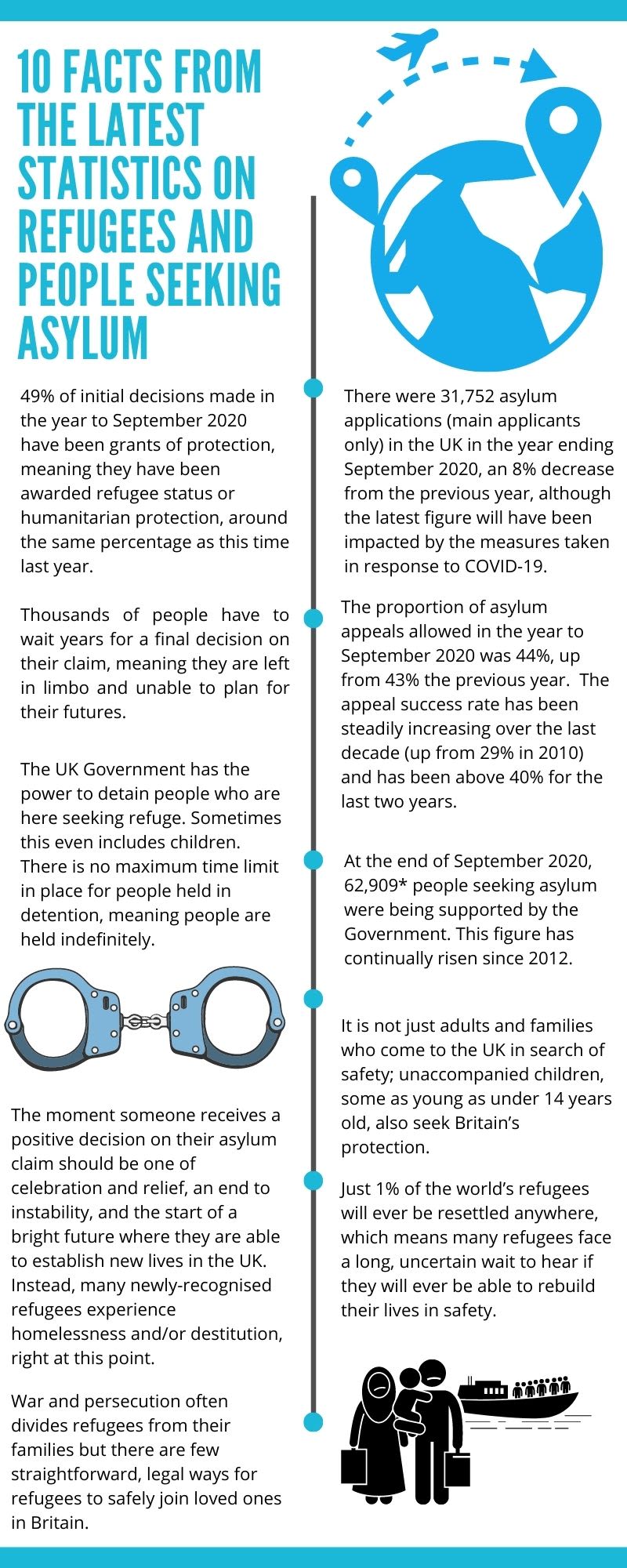

The refugee situation is an ongoing issue around the world. It challenges how we think about globalisation, multiculturalism and the very basics of free, open and democratic societies that hope to spread those values across the world. According to UNHCR statistics, at the end of 2019 there were 133,094 refugees, 61,968 pending asylum cases and 161 stateless persons in the UK alone. If we begin to look at what is happening in the Canary Islands just now, as it becomes a new destination after the inundations in Lesbos and Lamparusa, we can see that people who have no future in the global south (so-called) are on the move, more than ever, to find their way to the global north. Whether doors will be opened for them, the question of who welcomes them and who sees them as a problem to be resolved can only become a bigger and more important question, not just year by year, but month by month at this point.

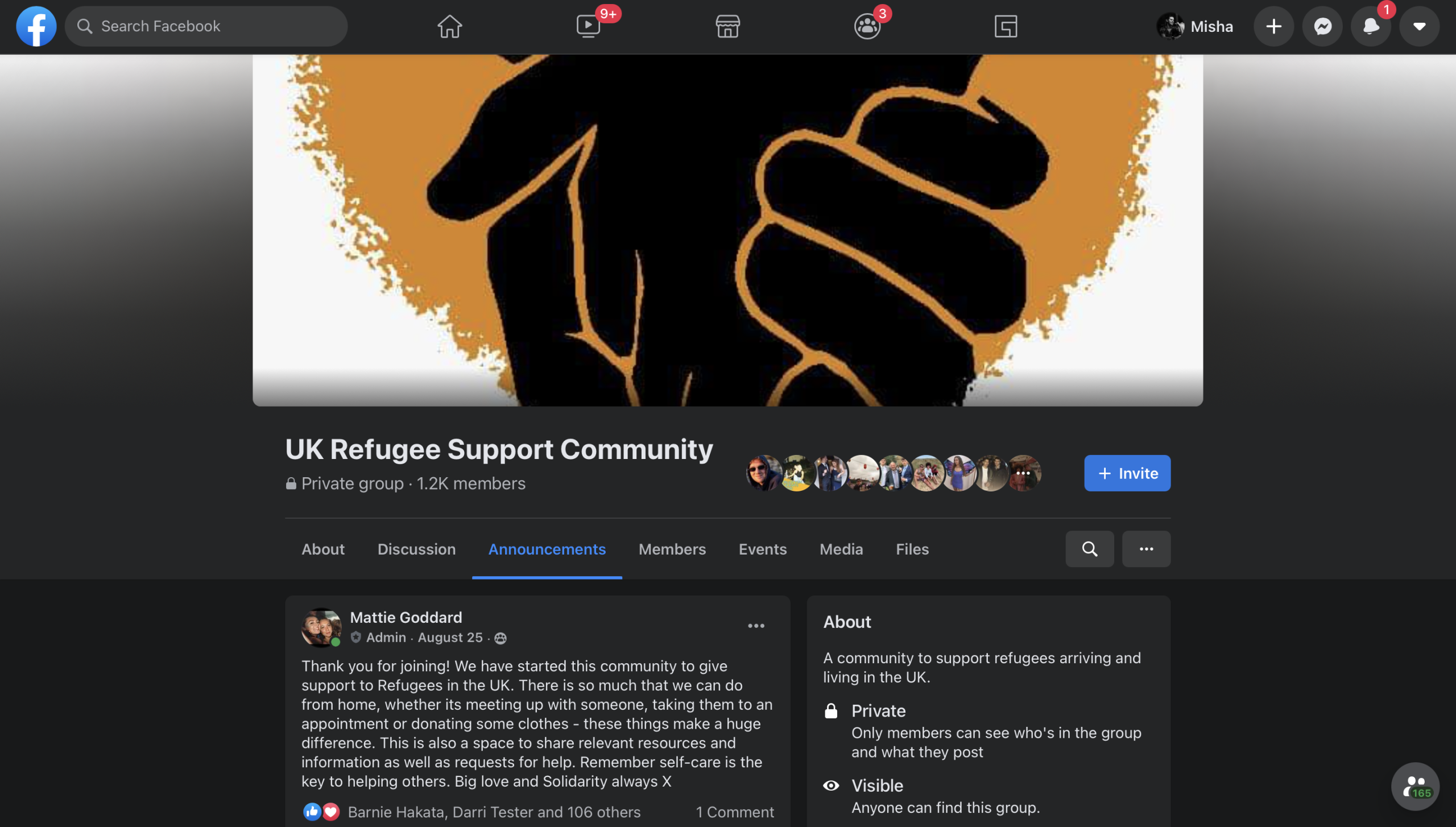

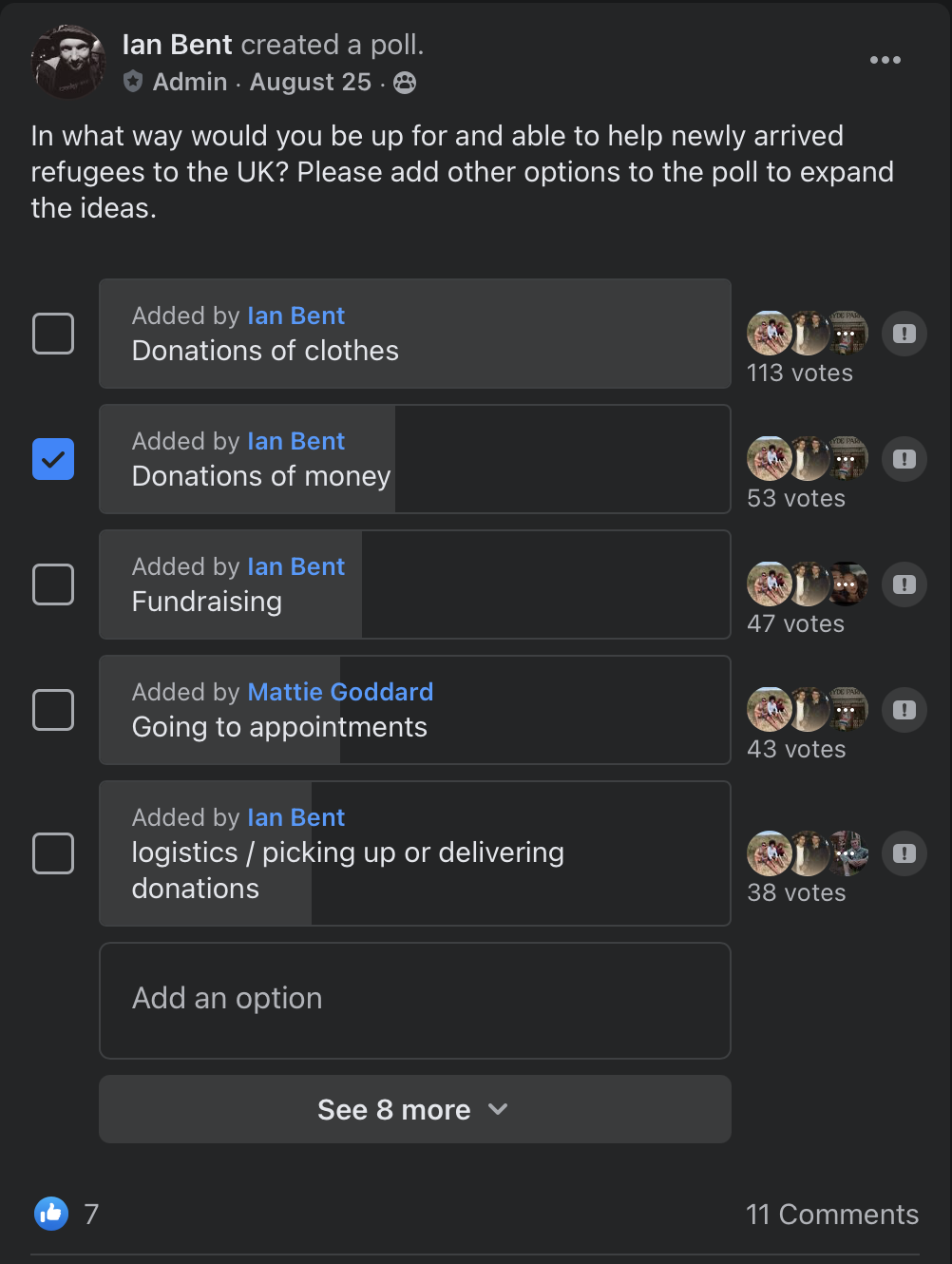

I wanted to find out how challenging the process of claiming asylum in the UK is for a refugee fleeing their home country, and I also wanted to know who’s helping refugees in their efforts both to settle in the United Kingdom in the first instance and supporting them once they’re here. ‘UK Refugee Support Community’ is one of many community online based groups that give the help and support refugees need. It is run by eight organisers, and while the group is fairly new, it has gained a remarkable 1.2k active members, including myself.

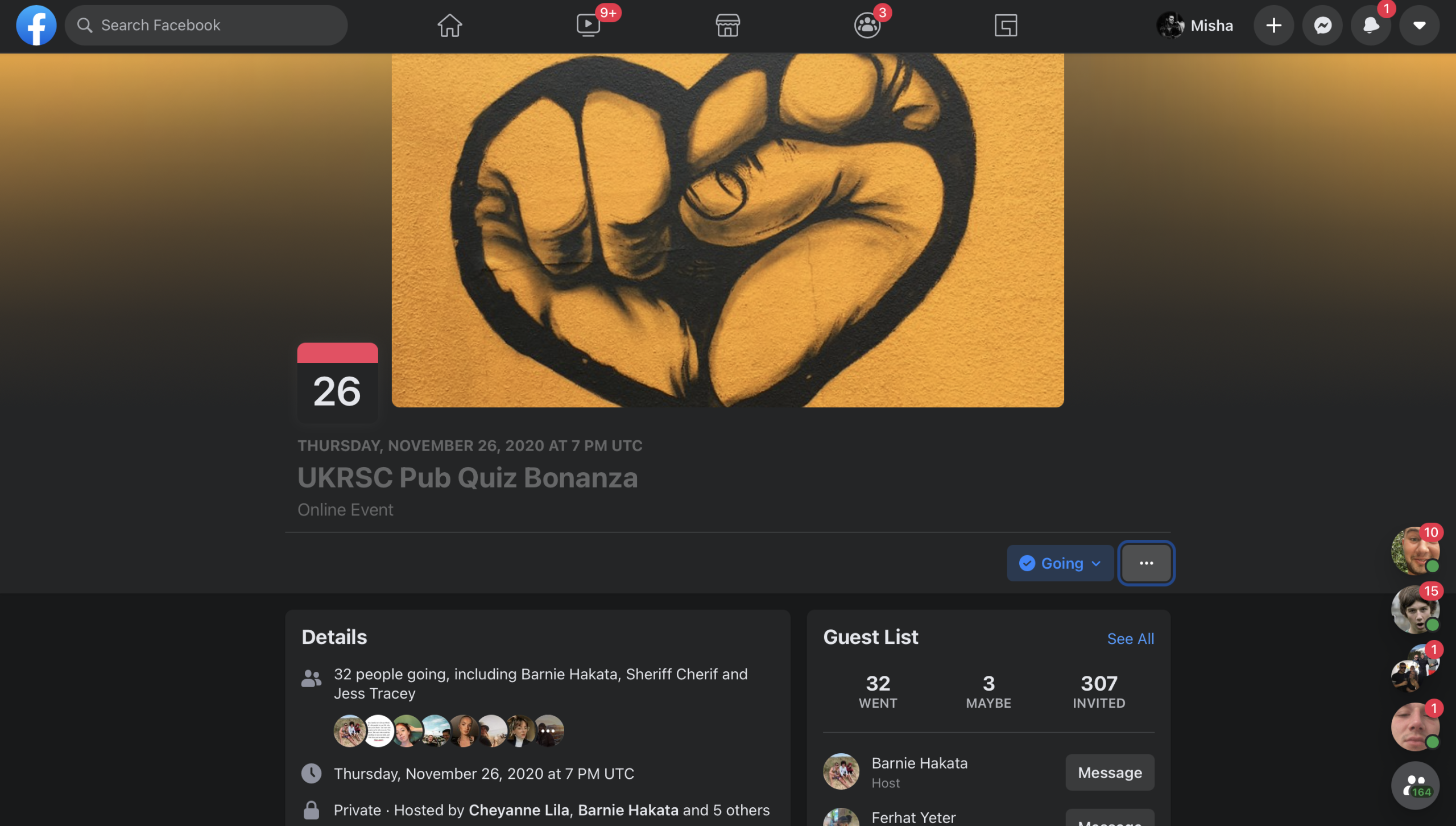

The main factor accounting for its success has been its ability to connect asylum seekers, who may have been placed anywhere in the UK, with an active member of the group that lives in the same city. From there, they can meet up if they have any initial needs, for example a phone or any particular clothing, help finding someone or getting somewhere. They also conduct various events such as online quizzes you can join for a small donation, which will then go towards buying essential items for refugees. Mattie Goddard is one of the founding members of UKRSC and below is an example of the kind of announcements she will upload and share.

I was able to interview Mattie Goddard to find out in detail what the future holds for ‘UK Refugee Support Community’.

When asked, when did you launch ‘UK Refugee Support Community’ and what were your main objectives in forming this online community/resource, Mattie explained:

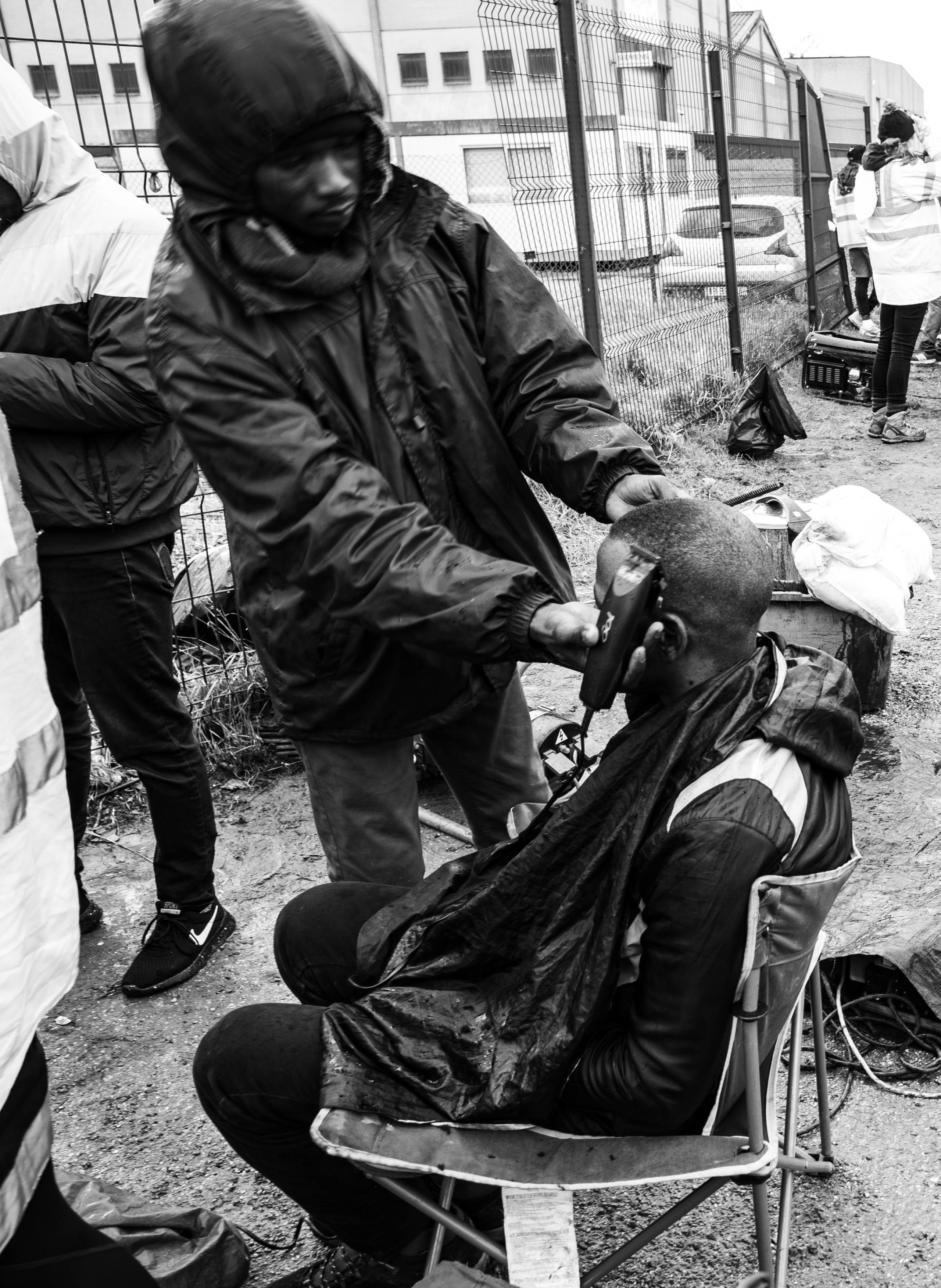

“Officially we launched UKRSC in August, but it has been evolving for a while. Barnie Hakata (the other founder) started adding people to a small Facebook group chat where we would post information, petitions, articles, organising trips to Calais etc and generally seeing who was interested in helping out. We decided to expand this group to a community Facebook page, and we are now a registered, not for profit CIC. Our initial objective was to show how much change people can make in supporting the Refugee community from the UK/home, also, that there is so much many people can do without having to give anything financially. We focus on using kindness and compassion as the drive to help. We can all do something, regardless of how small it may seem; having a conversation, sharing a petition, accompanying someone to the dentist, texting them, giving them a pair of old shoes – all of these things make a huge difference!”

Did you expect to gain as much support as you have? Is more support needed, and if so, what kind of support are you missing?

“Honestly, I continue to be amazed and insanely grateful for the amount of support we have gained, how strong the movement has grown, and how wide it has spread. What started as a small group chat is now a UK wide community, with over 1.2k people - which is so powerful! There are currently 8 of us who run UKRSC, and all are balancing Uni and/or work etc. More support is always welcome! We have some fantastic volunteers with us at the moment who have been a huge help in setting up some of our social media etc. There are so many people in the group who are so willing to contribute their time. We always need more people to get involved! We are working on some fundraising ideas at the moment as where physical donations can’t be given, there are a lot of crucial things that we need to get to people. Sharing of our content and social media sites is a huge help, and we have had an amazing response. It’s really important we have a big signal boost as we can get all the important information out there”.

Do you have any relationships with similar organisations or government bodies to help support your movement?

Where do you see it going for the future and are your short or long term what are your goals?

It’s easy to see the passion that goes into running a community like this. As she clearly states the smallest gesture from us could make a world of a difference to someone foreign to the UK. It’s very easy to see the open-ness, the desire to welcome and embrace new people in our communities who have fled impossible circumstances, in what Mattie and the other key figures in the group do. Rabar's story is one of many.

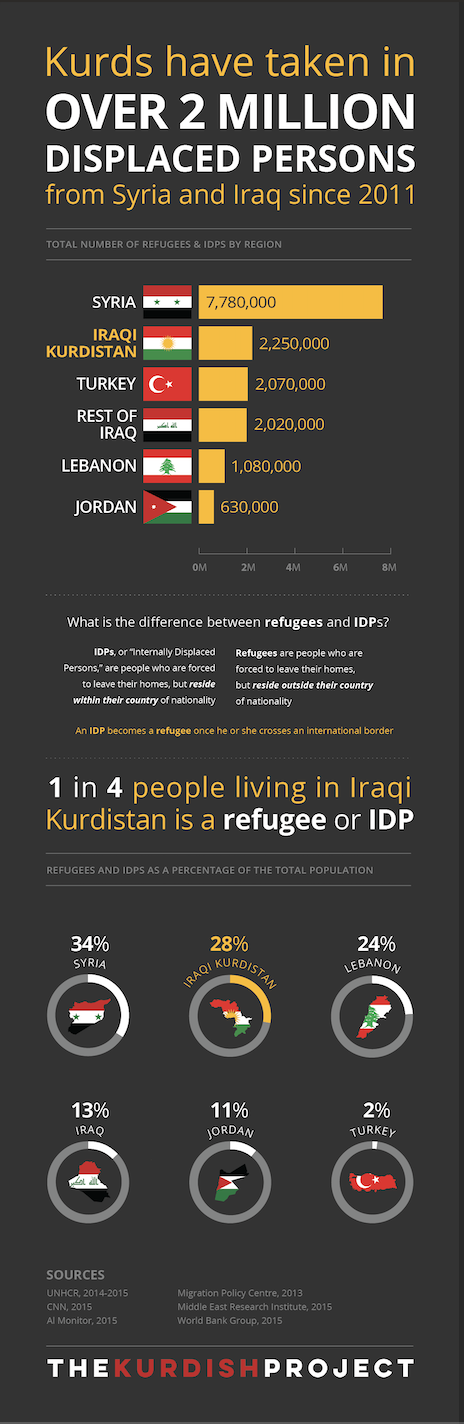

Rabar was born in Kurdistan and fled his country two years ago after speaking out about the harsh regime in his country, which in turn put his life in danger. I was fortunate enough to meet Rabar in Leeds when he came to visit a mutual friend of ours. To actually befriend and see the face of a refugee, facing persecution in their own country, and see how they try to find their way here in the UK, put the human face and friendship onto what the UKRSC are trying to do.

It's probably best to let Rabar tell his own story. While he still struggles with his English, it is startling how well he communicates after only two years here. It probably says a great deal about the resourcefulness and potential contributions many of the refugees and asylum seekers can bring to their new lives here in the UK.

As newly introduced friends, I was able to speak to Rabar and find out his story. After speaking to Rabar on the phone, I slowly got a better understanding of him, how he identifies himself, and his views and opinions on his current situation. Rabar comes from Kurdistan; that is his own description of his homeland. I had to press a bit to find out which bit of Kurdistan, ie., in which recognised state did he and his family live. The Kurds are an ethnic group spread across a number of middle eastern countries. The present ‘heartland’ of the Kurdish nation, known as Kurdistan, spreads across Iran, Iraq, Syria and Turkey.

Rabar is from the Iran section of Kurdistan. Emigration from Iran is, of course, not a new phenomenon. As Aljazeera wrote in their 2019 article, over the last four decades hundreds of thousands of Iranians have left their homeland, and over time they have constituted a diaspora of four million people around the world. Some managed to obtain the necessary documents and flew over to other countries to set up a new life. Some walked across mountains and jumped over barbed wires and languished in refugee camps before settling in a new home. He goes on to explain in more depth why it is he fled his home country in an interview I managed to obtain with him.

When asked, When and why did you leave your country?

How did you find yourself in Birmingham and did anyone help or support you?

What do you need now? What do you need to make a future in this country?

Do you feel discriminated against because of where you are from or is that not a problem

If and when you start your own family would you want your kids to be raised fully English or is it important to raise your kids in a similar way you were in your home country? and how are you finding your new life in Birmingham?

“I left my country about 2 years ago. I left my country because it became very dangerous to stay. The reason was because I, along with many others, spoke out against the harsh regime of the government and anybody that did that put their lives in danger”

“Birmingham wasn’t my choice. However, when I found myself and ironing, and I asked the people I was travelling with what should I do now, they told me go to the Home Office. So this is what I did. Home Office helped me to get in touch with social services and I received help from them”

“I need a decision from the Home Office as to if I can stay. Once I’ve got that I need an education, which will allow me to work as a plumber whereby I can earn an income to provide for myself and pay back the country that has given me my freedom back.”

“I can’t say I feel unwelcome, but on the other hand I don’t feel fully integrated.”

“If I was able to have my freedom back in my own country I would definitely go back and raise my kids there.”

“I like Birmingham in a lot of ways but there are some things that disappoint me. For example, I sometimes think social workers and support workers are in the job for the wrong reasons. They see us as a commodity rather than as individuals with individual support needs. It is that factor that disappoints me most.”

Rabar's story is not an unusual one. It talks about two things we all should think about in the context of the UKRSC network and the government organisations and workers who are meant to help people like Rabar find their way forward in this country. The first is the question of who opens the doors to refugees and how refugees in our country are understood by both our government and our society at large. The second is even more controversial. To what extent has the ongoing refugee crisis become a ‘business.’ I wouldn’t have thought about this if Rabar hadn’t mentioned it – feeling like he was treated like a ‘commodity’, like somebody who justified someone else’s job. That is an interesting question. We all know that war is business; it earns a lot of people a lot of money. And as the old joke goes, war is business, and business is good.

However, I never thought a great deal about how social work and re-integration efforts, or humanitarian efforts in conflict or post-conflict societies are also a sort of business. This is not to say that a great deal of that work isn’t wildly important – crucial even. It is just to say that if someone like Rabar feels like his way of finding a home, maybe temporary, in this country, means being a number, a case file and a commodity, maybe there is something we do not yet fully understand about the refugee experience. Many people want to help, to be sure, especially when they see people are forced into unknown circumstances. But making people feel helpless – dependent, a burden – as part of that ‘helpful’ process might make someone like Rabar hope that he can go home for more reasons than his identity and sense of belonging to Kurdistan.

However, first I want to go to the initial question. Who opens the doors in the UK and how does our government, its agents and the society it serves, think about refugees. On the face of it, Rabar is a ‘cosmopolitan’ by anyone’s standards. He has crossed borders and found new opportunities. He has learnt a new language, tried to integrate into a new culture, and he eats new foods. The question, explored in books like Whose Cosmopolitanism? edited by Nina Glick Schiller and Andrew Irving, raises the question about what being cosmopolitan means politically and in someone’s lived experiences. If people from Europe or North America are white and educated, and then move to find job opportunities, new experiences, new adventures, they are celebrated.

It is the happy face of globalisation. But that globalisation is Janus-faced. One side of the face is very white and the other very black. One side reflects the ingenuity of the global north and the other the desperation of the global south. It seems that, as with the days of empire, it is to be celebrated when white people find new opportunities in foreign lands. We seem not to like it so much when people from the global south show up on our shores. Suddenly, this other side to globalisation does not look like cosmopolitanism but like a virus – something we have to keep out like Ebola or Covid-19. Maybe we, in the global north want our cosmopolitanism as long as it doesn’t cut both ways.

Schiller talks about a training programme, where participants came from Afghanistan, Libya, Yemen, Pakistan, Iraq, Congo Zambia, Sri Lanka and Sierra Leone. The training programme was about climate change, in their countries of origin and in the country (the UK) where they had re-settled. From the way Schiller set things out, it seemed, these people were a good ‘resource’ for constructive dialogue. However, listen to this:

“In conversations over lunch or on the way to the bus stop, I asked the various participants about their views about living in Manchester. As they packed up any leftover food to take home, I heard about issues of hunger and the difficulty they faced in feeding their children. Each of the individuals spoke of their efforts to find legal status, education and adequate employment in the city. […] In these conversations, the refugees positioned themselves variously and multiply as parents, students, un-employed professionals, religious persons, members of transnational families, Mancunians (people belonging to the City of Manchester) and people interested in social justice.”

All of this speaks a great deal to my interviews with Rabar. So many ways of identifying oneself, and none of them entirely satisfactory, because it is hard to choose between being here and being from ‘there’. Rabar has no contact with his family at present. Yet he wants to return someday to raise his children where he was raised, if that becomes possible. At the same time, he wants to belong here, and not just in the sense that he can manage to get by day to day.

With regards to our interviews with UKRSC, Schiller also tells us something important.

“They also spoke of their connections to individuals in refugee support organisations in the city with whom they had forged social connections. Whatever their initial motivation, it became clear that the refugee participants’ involvement with the issue of climate change grew as the training went on, and they discovered that, through their memories and through accessing family members within their transnational networks, they had knowledge about changing weather, floods, droughts and crop conditions ‘back home’."

It is not for me to say that rabar has a great deal to say about global warming. It is not for anyone else to say that he might not!

As Walter Mignolo wrote, the ‘West’ is not a geographical place. It is a language family, a set of beliefs, a way of being. And it is happy to colonise other places but expects people to conform to its ideas at home or abroad. Unfortunately, this place, the ‘West’, which we cannot find on a map because even if we call it the global south, we cannot avoid that places like Australia and New Zealand don’t seem to be west and they are pretty far south, has been a big part of how we have created an interconnected world. What happens elsewhere, happens here as well. The Covid-19 pandemic put that into stark relief.

So, Who’s Cosmopolitanism? That is the question. Hamid Dabashi puts it well when he says: “If one is not global, one is not local, and if one is not local one is not global. The most boring and irrelevant intellectuals are those who think the US, Iran, India or the North Pole are the centre of the universe”. It seems like the west – or the global north - wants to have the corner on the market of being both local and global all at the same time. When refugees and asylum seekers show up on our shores, they bring their local ways and their locally inspired needs.

They bring their push to the call of our irresistible pull – as they say in migration studies. However, when ‘we’ show up on their shores, it seems to be the opposite. ‘We’ bring civilisation. Our local is the global of the future. What ‘we’ bring is cosmopolitan, and it connects the world for better or for worse.

Dabashi mentioned Iran, which is very much at the forefront of the news right now, as most of the international community sanctions the country. They worry about it possibly developing nuclear capacity and shun its non-secular politics. So, the story of Rabar tells us something about how cosmopolitanism works in the context of people pushed from their own ‘local’ to find the ‘global’ that the ‘west’ says it promises.

In another interview with Usman Ali, who currently works with ‘I Have a Voice’ and recently wrote a brief about the most recent 82 arrest warrants issued by Turkey against Kurdish activists, he stated that he couldn’t understand “what is our [the UK’s] stance with these things. Why are we not taking a more human approach?" He suggested that the government have at their disposal “histories, lives […] but the government doesn’t want to engage with this.”. He suggested that the Windrush scandal and the ‘hostile environment’ introduced by the past Tory government, might be an index of the extent to which our current government might be willing to take on situations like the one in which Rabar finds himself.

Usman Ali’s comments on the Lloyd offers some background.

“The Kurdish (commonly referred to as Kurds) are a community of approximately 18 million people, who are geographically dispersed across Iran, Iraq, Syria, and Turkey. Since the First World War, the Kurdish community have been, and continue to be, one of the largest stateless groups in the world, making this issue pertinent and of contemporary relevance. They have been actively campaigning for a state since the late 1800s. In the early 20th Century, many of the Kurdish community began to consider the creation of a homeland - generally referred to as. After World War One and the decline of the Ottoman Empire, there was initial provision and discussion for a Kurdish state in the 1920 Treaty of Sevres. However, in 1923, such hopes were dashed in the Treaty of Lausanne, which established the borders of what is now Turkey, and subsequently, made no formal recommendation for a Kurdish state. In addition to no provision of a Kurdish state, the Treaty of Lausanne did not protect Kurds with minority status in their respective countries.”

This background is important. Rabar identifies himself as Kurdish and coming from Kurdistan. It took further questioning to find out in which recognised state he came from, which rather matters in terms of his status in legal terms. Kurds were US and UK allies in the fight against ISIL in the north of Syria. Turkey then declared these same Kurds as ‘terrorists’, and the Kurds' allies in other parts of the ‘West’ were more than a bit shy about confronting Turkey about this decision.

The point for Rabar and for the UKRSC is about how to make people like Rabar feel welcome in a country where they are getting mixed messages. Material help and a sense of support and solidarity is crucial, and organisations like UKRSC can provide that. But what does one do when some of the most basic support, including pursuing a proper legal status, needs to come from a government that seems equivocal about their right to be anywhere? What does Rabar do when he expresses his interactions with social workers as being not even a client, but rather a commodity?

As UKRSC expands, it faces these very challenges. It, like Rabar, faces the complex world of geopolitics. Unfortunately, people get caught up in the middle of these politics, so coats, food and advice are not always going to be enough. The organisation was not started as a political movement. It was simply meant to open doors and welcome refugees who come from difficult and often traumatic backgrounds entwined with the countries from which they have escaped. As Rabar said, they are not countries they want to abandon. They dream of return. They dream of families with whom they cannot be in touch. They dream of raising children in their culture and their religion and their histories, whether in Great Britain or back at home. Surely, in a multicultural country like Great Britain, such things should not be impossible to imagine. For Rabar, and the UKRSC, and for advocates like Usman, the question must be about how to marry practical support with the sense of belonging that only a different kind of politics could offer to these people.

We know that Rabar has made every effort to settle and integrate here in the UK. We know that certain organisations have tried to open the doors of our country to him and make him feel welcome here. And yet, we also know from all of these interviews that there is still so much left to be done.

Rabar has managed to learn English in just over two years. Can it really be so hard to learn to speak his language (metaphorically speaking) in at least the same time? His future, here or in the Kurdistan he imagines, rather depends on it.